E!TACT! #22

Justice League #43, Batman #45, The Terrifics #3, Batman and the Signal #3, Hit-Girl #3, Justice League of America #29, Grunion Guy's Musical Corner of Music Reviews, and Letters to Me!

By Grunion Guy

Comic Book Reviews!

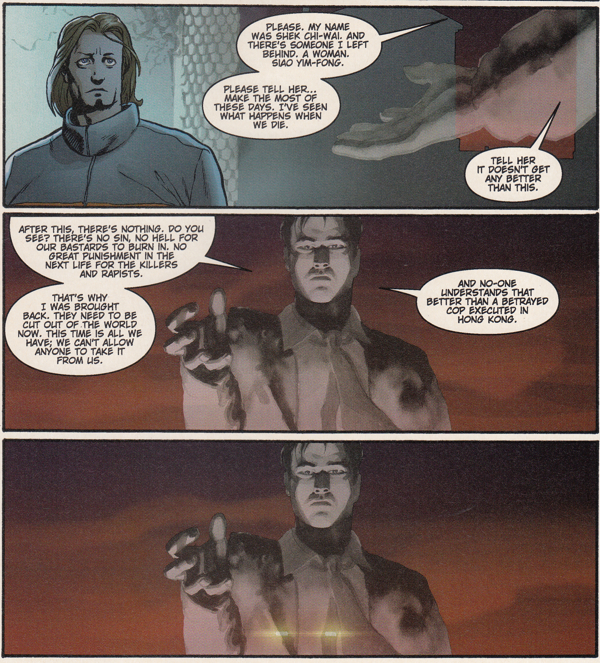

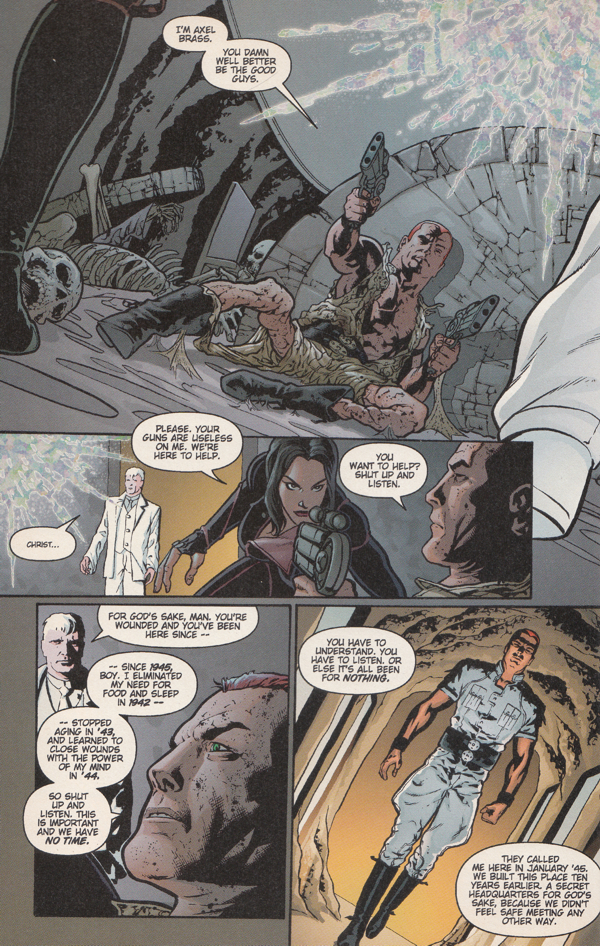

Justice League #43

By Priest and Woods

Last issue ended with Deathstork murdering The Fan, the guy who knew all of the Justice League's secrets. Superman and Batman both scolded Deathstork for murdering a guy in cold blood but Deathstork defended himself by saying, "You all know...." That was as far as he got before Batman was all, "You're right! Let's talk about something else now, maybe something that isn't also how we're not going to arrest you. I mean, you had a very convincing argument when you asked, 'Did you actually see me kill him?' after which, I'm assuming, you winked."

See, Deathstork only has one eye so you can't really tell if he's winking or not. Did you get that joke? Was I too subtle? Sometimes I'm way too subtle which is funny because most of the criticism I receive from boring people is that my reviews aren't subtle. But then, those are people who actually believe I'm reviewing comic books.

Deathstork and the Justice League begin to fight because a newscopter comes along and the Justice League are all, "We'd better make this ooklay oodgay!" (They speak in Pig Latin so the newspeople can't understand their plan to trick them.) During the battle, Deathstork calls Batman a pacifist. I think maybe Deathstork needs to buy a dictionary. Deathstork may have killed more people than Batman but I think Batman has broken more bones in other people than Deathstork has. And not from hugs, you dum-dums who also think Batman is a pacifist. I could see how it can be confusing though. Batman does hit a lot of people with his fist so at first I was thinking, "Oh yeah! He's totally into pack-a-fisting things!" Then I was all, "That didn't make any sense. Maybe I should buy a dictionary."

Cyborg's plan which he doesn't explain to the readers but the readers know what it is (especially when the reader is me) is to have Deathstork defeat the Justice League on camera so that everybody will run away. That solves the problem somehow. Maybe it's like putting a club on your steering wheel. It's not really that effective at keeping a thief from stealing your car but car thieves see it and just move on to a car without one simply because it's easier to drive a car without a club on the steering wheel.

Even if you were one of those reviewers at Weird Science, you'd probably have realized that the Justice League was throwing the fight because Aquaman was knocked out when Deathstork threw Batman into him. I know Aquaman is lame but comic book physics still have to apply. If Batman was really hurled into Aquaman, Batman's neck would break and Aquaman's nipples have a slight possibility of getting hard. Also, I just read Weird Science's review of this and they totally didn't get the plan until it was explained later.

After everything is sorted (well, sort of sorted), Cyborg asks Batman (after punching him in the face (which is the best time to ask Batman questions)), "Did you bring The Fan to Africa to die?" Batman doesn't answer the question which is the only answer I needed for my question as to why Batman and the others let Deathstork run free. They definitely approve of him killing the people they need killed. The only reason Batman gets so annoyed when Jason Todd or Batwoman kill is that they're ruining his brand. But Deathstork? He's the perfect tool for ridding Batman of sticky problems.

Rating: 8 out of 10 stars. Priest gives the Justice League some ethical problems to work through and they don't really work through them. But that's the nature of comic books. The story is just to give the readers a glimpse at one aspect of being a member of a global force for good and how it's used. It's like asking that stupid question, "If God is omnipotent, can he create a rock so heavy he can't lift it?" You can't really answer the question. You can just present it so that people go, "Oh yeah! That's a right corker!" Then maybe you can say some things that make it sound like the question has been answered so people leave you alone afterward. But mostly, Priest's story is just one of those stories to say, "You know why the Justice League doesn't fix everything? Because they can't! Duh! Now forget all of that grey stuff because they need to white the universe from black!"

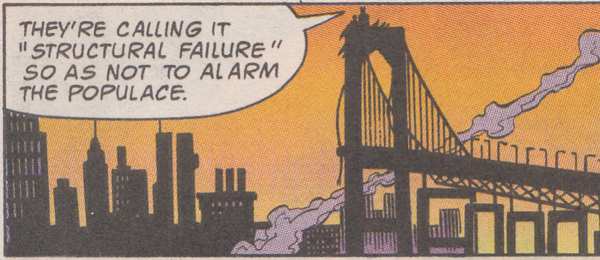

Batman #45

By King, Daniel, and Morey

Rating: 9 out of 10. That might be a little high but it's because there's something I really like about this issue. It's a time travel story which I usually hate. But it's a time travel story which shows why time travel stories are so dumb. In this issue, Booster Gold goes back in time to save Bruce's parents so that Bruce can experience the terrible world that would result from that having happened. Then when everything goes back to normal, Bruce will be all, "Oh yeah! I'm glad my parents are dead! Thanks for such a beautiful wedding gift!" (Oh yeah. The premise is that this is Booster's wedding gift to Batman.)

So anyway, Booster fucks it all up because Booster is an incompetent moron. Which, I'm assuming (almost certainly correctly!), is King's metaphor for how people who write time travel stories are incompetent morons who always ruin everything! "But how could it all go wrong?" you sad losers ask in a sad and loserish way. Because Booster Gold forgets how much Bruce loves his parents! So when Bruce learns the truth, he smashes Skeets so that he can forever live in a terrible timeline where Ra's rules Eurasia and people turn into Jokers on a daily basis in Gotham and Dick Grayson is the biggest 90s Image superhero ever! And of course, now it's up to Booster Gold to fix everything! What a dumb jerk (just like all the writers who write terrible time travel stories! (which maybe now includes Tom King? Oh man! Is that the biggest time travel paradox yet? That I love Tom King's Batman but I hate time travel stories so now I hate Tom King and/or love his time travel story?! (I'm confused. How many parenthetical references has this been?)))!

Booster Gold is more enjoyable in this issue than he is in any issue Dan Jurgens has ever written. That's because Tom King presents him more as the Giffen and Giffen's pal (you remember him! The guy who wrote Moonshadow!) version of Booster. He's a bit of an incompetent dork. That version was always much better than the one where Booster Gold is the sheriff of all time and the most important character in DC continuity.

I still maintain that people who dislike Tom King's Batman have no sense of whimsy and do not enjoy actual story-telling. They just want standard continuity and no risks Batman stories that remind them of all the other boring Batman stories they've read over their sad and pathetic lives reviewing comics at the Weird Science blog.

As a story teller, Tom King might be one of the best comic book writers around. Maybe he's not the best writer or the best at allowing fans at cons to give him oral sex. But he tells entertaining stories. I suppose if you have a continuity stick up your butt and you expect characters to rigorously represent all of the facts listed in DC's Who's Who, and these things force you to scowl and dismiss any enjoyable story that doesn't maintain those standards, I can see why you're stupid. I mean why you don't like Tom King's Batman. Sorry that I just repeated myself there.

The Terrifics #3

By Bennett, Lemire, Hope, and Maiolo

Excuse me, DC? DC? Can I get your attention for a second? I just wanted to clarify something about this whole Dark Nights Metal off-shoot comics thing you're doing? Weren't each of these series supposed to excite the audience by tying the best writers with the best artists? And wasn't this supposed to be the book where Ivan Reis spread butter all over my inner butt cheeks so he could more easily bring me to orgasmic bliss? Because I just looked at the cover through a haze of butter that dripped into my eyes and I'm fairly certain Ivan isn't the artist here. And it's only, you know, the third fucking issue? DC? DC? Where are you going? Aren't you going to answer my question?!

It's a good thing I don't purchase my comics based on who's drawing them. That's the immature way to pick comic books and I'm the exact opposite of immature. Although my favorite moment in Batman #45 was when Booster Gold busts into Bruce's birthday party (unless it's his parents' anniversary party (it might be both!)) and says, "I got you a present, Batman!" Then Skeets is all, "Bruce Wayne." And Booster shouts, "I got you a present, Bruce Wayne!" I suppose if I really were mature, I wouldn't have thought that was funny because it wasn't in iambic pentameter and it didn't subtly refer to a penis.

Another piece of evidence that doesn't support the opposite of immature theory is that my favorite part of this comic book is Phantom Girl's butt.

I mean, sure, it's no Supergirl's bum. And it's not Ivan Reis's Phantom Girl's butt. But it will do, pig. It will do.

I mean, sure, it's no Supergirl's bum. And it's not Ivan Reis's Phantom Girl's butt. But it will do, pig. It will do.Rating: 4 Phantom Girl Butts out of 6 Supergirl Bums. This comic book is comic booky. That's the adjective I save for comic books that I can simply enjoy as comic books. They aren't trying to be anything else and I admire them for that. They've accepted their place in this universe in much the same way I haven't accepted mine. They're better than I'll ever be.

It's just so nice to be able to read a comic book that doesn't make me think nor does it make me think that I should be thinking. Sometimes I want to read a difficult comic book so that I can sound smart when I talk about it. But have you tried finding a difficult comic book?! I might as well be looking for a dick that has been inside of a vagina after I've time traveled to an early eighties San Diego Comic Con. Of course if I did find one, I'd know that I messed up the calculations and landed at a 70s con. Lucky sex crazed bastards.

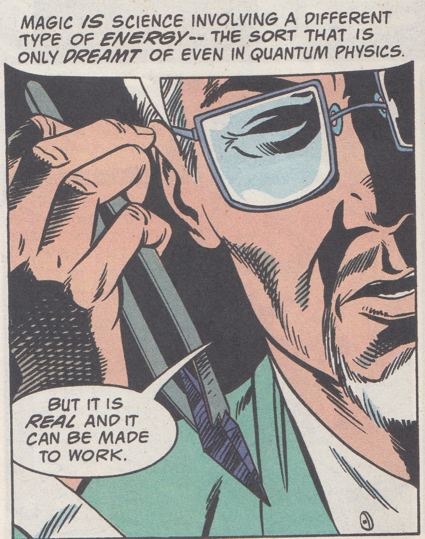

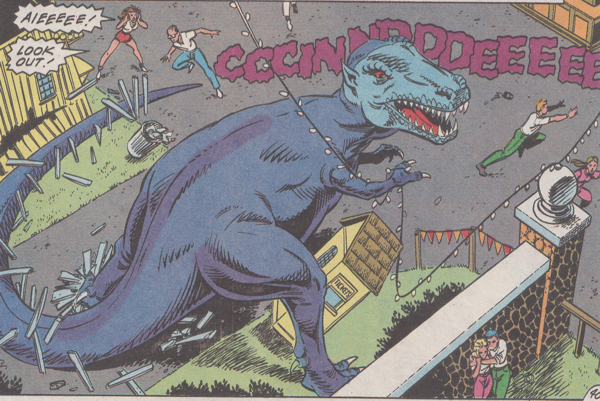

Batman and the Signal #3

By Snyder, Patrick, Hamner, and Martin

This issue begins with Jason Todd saying, "I know you think he's always on time — but in my experience, Batman's always been a little too late." Geez, Todd. Get over it already! So one time he didn't save your life! You can't constantly judge a person on one mistake! You have to wait until they've written twenty or thirty issues of New 52 Teen Titans before judging them constantly! Also, don't go back and read my reviews of Scott Lobdell's Teen Titans because they might expose me for a judgmental hypocrite who immediately started judging Lobdell one-third of the way through the first issue.

Later, Duke Thomas learns that he's a Jesus figure in both the Christian sense and the sun god sense. Duke's family history mirrors Jesus's while the emphasis of this entire story is on the role of daytime in Gotham.

And now, a short dramatic scene in a bar after James Tynion IV had one beer more than he usually has!

Scott: "Have you noticed how nothing ever happens in the day in Gotham, James IV?"

James: "What? Of course stuff happens in the day. Sometimes the Joker even attacks in broad...."

Scott: "Right. So I was thinking, 'What if Gotham had a hero that went out during the day?'"

James: "Like the way Batman sometimes goes out during...."

Scott: "And everything can be day-themed! Like his nemesis can be The Sundial! No, no! GNOMON!"

James: "That's great, Scott. Genius. So smart."

Scott: "Thanks, James IV. But is it enough? It needs a little more of a hook, especially since I'm thinking of using Duke as the day hero. He's already the most boring Bat-kid. How to spruce him up?"

James: "Maybe he's bisexual? And he's got a bit of a crush on his mentor? And maybe one night he drinks one beer more than he usually does and expresses his passionate love for him?"

Scott: "Oh! That's a great idea, James IV! Make him a Jesus figure! That way we can reference how special he is and how he's The One and how he's super important to the DC Universe no matter how boring he is!"

James: "Um, yeah. That's, um, exactly what I just said. I love you."

Scott: "Did you say you drug Jews, James IV? What the hell is wrong with you? Do you want a bi-line on this new series I just came up with? And did you get my joke? I said 'B-I-line' instead of 'B-Y-line'! Because you're bisexual!"

James: "Can we get the check? I have to go home now."

Rating: 2 out 5 Sundials. Signal is an appropriate name for Duke Thomas because it's such a boring name. And just to be clear, half of the Sundials I awarded to this issue were because the series was only three issues long. Thank Thomas for that!

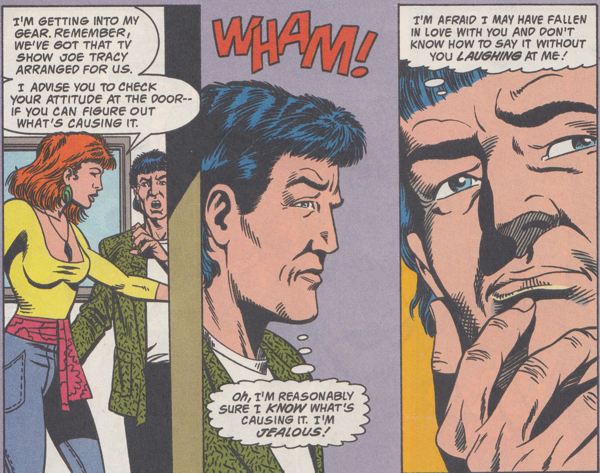

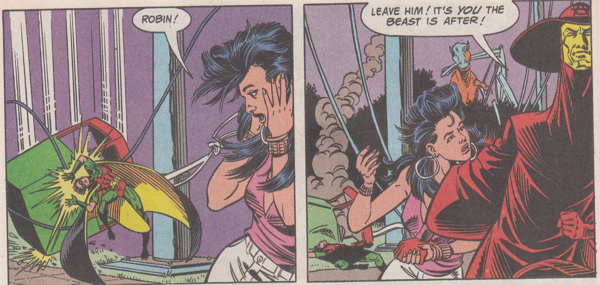

Hit-Girl #3

By Millar and Lopez Ortiz

This is the issue where Kick-Ass Hit-Girl wades in a little too deep and winds up captured by the people she's been mercilessly slaughtering. You can't have a realistic non-comic book comic book about violence without the hero feeling the threat of death at some point. But being this series is only four issues instead of the usual six, it's also the issue where she escapes capture! Because in the end, even a non-comic book comic book is still a comic book. Nobody wants a real non-comic book story about a violent vigilante because it wouldn't even have enough story to fill one issue before the double-sized final funeral special.

Rating: I still don't like the art although it's probably appropriate for an over-the-top violent comic that relies on proclaiming how cartoony it is or else it would simply be too vulgar for the general population. And when you rely on the general population being thrilled by movies based on your comic books, you have to ease into the super violent territory. Although, I suppose, that argument doesn't really work because the movie this will be turned into will be quite realistic and still have just as much violence and people will love it. That's probably why they had to add the theme to The Banana Splits to Hit-Girl's most violent scene in the first movie. It made it more cartoonish and thus acceptable.

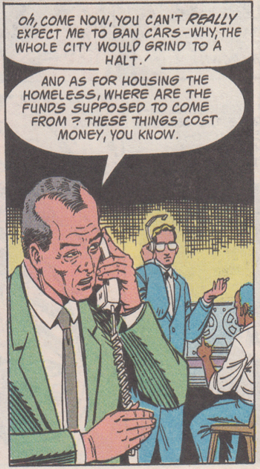

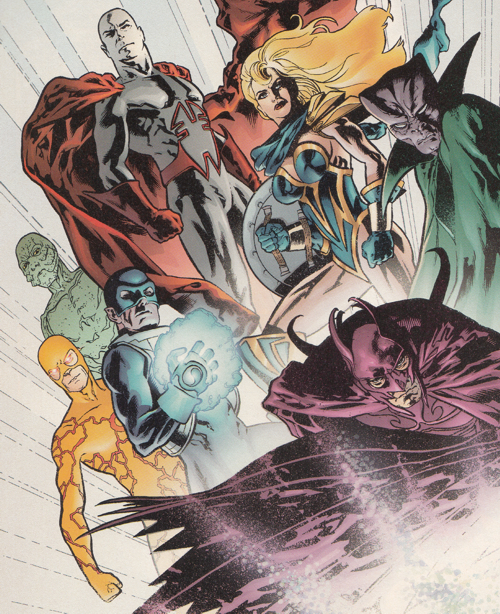

Justice League of America #29

By Orlando, Petrus, and Hi-Fi

At some point in the last few months, some higher-up at DC Comics decided that every comic book they publish should be part of the canonical DC Universe. I think somebody in charge finally read some of Grant Morrison's comic books and thought, "I have a great idea! We should simply allow writers to acknowledge anything we've ever published in the stories they write!" They didn't notice that their eyes began glowing red nor could they have known of the sudden erection that appeared in Grant Morrison's pants. Three of the children's souls Morrison keeps in jars in the pantry dissolved into blessed oblivion as his spell took hold. Now Tom Strong has appeared in The Terrifics and The Watchmen are crossing over into regular DC continuity and Promethea guest-starred in JLA and all the Young Animal imprints crossed over with Batman and Superman and Wonder Woman and Danny the Street was used by Chronos to kill Ahl whose first appearance was in the new Doom Patrol and all of Catwoman and Batman's suit changes throughout DC history were showcased in a recent issue of Batman. It's just the kind of thing that makes continuity nerds shit themselves because now they have to accept that Batman pissed his pants thanks to a throw away Kevin Smith line in his and Walt Flanagan's Batman book.

Don't worry about me though! I'm not one of those nerds! I'm the kind of nerd who thinks every single thing that ever happened in a comic book character's long existence should be part of their baggage. Even if fans hate it or it's problematic or it was such a huge miscommunication between the artist and writer that now Hank Pym is a wife beater. I'll accept anything as continuity since that can only help the case that every Captain Carrot and the Amazing Zoo Crew story has happened in the same universe as Bruce's parents being brutally murdered in an alley.

I'm also pro anything that gives Grant Morrison an erection.

Some people might not think that this is a radical position to hold or that I'm not sacrificing anything by embracing it. But remember that in my comic book philosophy, every story by Scott Lobdell and Ann Nocenti have actually taken place! You have to take the good with the bad. And also the bad with the worst which is, of course, Cullen Bunn's versions of Lobo and Aquaman.

This book ends with Justice League of America becoming the Justice Foundation. That means they'll be using their powers and resources to make the world a better place. I'm assuming the first order of business is to license their teleportation technology to the rest of the world? And maybe to put Alfred's healing tea on sale across the country? What about Lazarus Pit technology? Is that ready for market or does everybody return with insatiable blood lust? Would that even be noticeable in America?

Rating: 4 out of 5 Lobos. Speaking of Lobo, he made an appearance in this issue (which is why the issue received such a high rating (I'm not like one of those totally subjective reviewers who constantly proclaim they're objective. I know I'm subjective (and when I say I'm objective, it's obviously a joke. I can't believe how often I refuse to explain that to idiots who comment on my blog))). It was a strange guest appearance because everybody knows Lobo is a genocidal maniac but still The Atom sends Chronos to be punished by Lobo! It doesn't make any sense unless Orlando is writing a super soft version of Lobo who respects Batman's no-killing rule even when he's not on the team. Or an even softer super soft version of Lobo who made friends with The Atom and respects Atom's opinions and his way of life enough to simply beat Chronos badly instead of killing him. Orlando's Lobo isn't as bad as Bunn's Lobo but he's really skirting the edge. The edge is that place where I read a comic book and then attack the writer's grandparents for giving birth to parents that gave birth to that writer.

* * * * * * * * * *

Grunion Guy's Musical Corner of Music Reviews!

Slave Girl by Love/Hate

This is the kind of song that, upon hearing it begin, your parents might say, "I'm happy to hear you listening to the kind of music we loved! This is that freedom rock, right?" Then the voice the singer uses throughout the album that he doesn't use in the beginning of this song screeches out of the speakers along with the heavier guitar riffs. Suddenly your parents make that face which indicates young people's music is terrible but they don't want to seem uncool so they don't say anything except an involuntary tut as they clutch the pearls that aren't actually there because they spent all of their money raising a musical heathen.

That description only actually works if this is the year this album came out. Which was nearly thirty years ago. Although since everything is now topsy-turvy, it's possible this song is being played by parents while their children have that reaction. It does have the chorus "She's a gang-bang slave girl. I'll be your home boy," which seems like lyrics that didn't move any kind of outrage dial on our generation but might get a young person today to say, five or six times in one breath, the words "problematic" and "gross" with a side-helping of "cultural appropriation" (because it is a white guy saying "home boy," maybe? I seldom can figure out the reason for offense these days. Maybe young people just react violently to older generations showing any kind of joy).

I just remembered that I had Love/Hate's second album but I can't really remember it. That's probably fine. The album this song was from, Blackout in the Red Room, was huge in my life in my late teens. Now I generally skip most of the songs when they come up on my shuffle. The whole album just feels like it should be heard while hanging out with friends drinking too much Jack Daniels. When I'm at work, it just doesn't give the right energy.

Grade: C+.

Tupelo by Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds

This song makes me a little bit sad. It begins "Lookee yonder. Lookee yonder. Big black cloud come. Big black cloud come." I used to sing it to my cat Judas: "Lookee yonder. Lookee yonder. Big black cat come. Big black cat come." Then I would change Tupelo to Jupelo which became one of his nicknames.

Speaking of Judas's death and current non-existence in the universe, the other day, the Non-Certified Spouse was searching YouTube for videos where cat's squeak like our Pelafina on the living room television via the Xbox. When she couldn't find any, she searched for Turkish Angora cats because that's what we suspected Judas was. She found a video of a cat named Precious who looked almost exactly like Judas. As we watched, Pelafina (who loved Judas as her brother-mother, having suckled on his male nipples when she was just a kitten and he was about a year old) noticed. Her tail poofed up a bit and she crawled toward the television watching Judy's doppleganger cross the screen. After a few seconds, she was distracted and turned away. Her tail returned to normal (unlike when something frightens her and it takes a while to return to its former size). But as the action on the television changed and Precious began moving around again, she looked back and her tail poofed up as she walked right up to the television to take a look. It was both the saddest and most joyful thing I've experienced in a while.

I've always wondered if Pelafina remembers Judas since most of her time was spent trying to encroach on his space and get him to put her in a headlock as he licked her roughly. She loved him immensely. This seems to confirm that she remembers him since the only other time she reacted so strongly and instantly to images on television was the opening to Constantine (which must prove she's from Hell, I guess?). But now she must think that we've locked Judas away in some kind of Phantom Zone where she can't cuddle with him. I bet she hates us so much right now.

Oh, I was supposed to be reviewing this song, wasn't I? Well, it's a Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds song. If you know their stuff, you know exactly what that means. If you don't, maybe this will help you: Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds' music sounds like your car broke down on a deserted highway where the only building nearby is a haunted lounge run by hipster vampires who haven't paid their electric bill so they run everything on a generator which causes the lights to dim and brighten at random intervals. As you approach the building to see if you can get help, a pack of a dozen itinerant and dirty people come out of the shadows and begin slowly following you while chanting in a barely audible whisper that steadily rises until they're shouting in your ear and you have a mental breakdown.

Grade: B+.

Under My Wheels by Alice Cooper

This is the first song on the album Killer and it might be one of the all-time greatest opening album songs. But before I discuss why that is, can we take a look at that cover?

Remember that project in first grade where the teacher takes a picture you've drawn and gets it transferred to a plate? This looks like Alice's.

Remember that project in first grade where the teacher takes a picture you've drawn and gets it transferred to a plate? This looks like Alice's.If an album called Killer on a bright red background with a snake that is both a phallic symbol and makes you think of oral sex because of the tongue didn't enrage your parents in 1971, having to hear "Under My Wheels" blaring out of your room must have pushed them over the edge. Aside from the driving guitar and thumping rhythm that obviously says, "I'm old enough to be thinking about sex constantly, mom and dad!", this song is either about a person running over their lover or being driven so maddeningly out of their mind by their passion for this person that they will run over everybody in town to go fuck that person. It's hard to say what "I've got you under my wheels" actually means. You would think it meant Alice was having some serious car trouble.

And if your parents weren't completely driven mad at that point, the second song on the album, "Be My Lover," probably finished the job. It pulls them in by making them think, "Oh, this album isn't so bad at all. It's a bit country and blues, I guess!" Then the chorus is all, "If you want to be my lover, you'd better take me home!" and your parents' heads blew up as they kicked in the door and screamed, "NOT IN MY HOUSE, YOU UNGRATEFUL WRETCH!"

Grade: A-.

Skips a Beat (Over You) by The Promise Ring

If The Beatles or The Monkees were still alive and had heard this song, they would have killed themselves over not having written it themselves (or, in The Monkees' case, they would have killed their song writers (I mean right up until they wrote their own songs!)). I'm not sure a more perfect pop song chorus exists. Too bad it exists in the same song as the verses which are lyrically like stepping in dog shit when you're too drunk to care (I wonder if my music review metaphors to describe songs are as universal as I think they are?). I mean, they're not bad in the way stepping in dog shit is always bad. But they're kind of annoying that they've happened and they're messing up your walk home where you had planned to just collapse in bed and sleep blissfully but now you're going to have to do something about this mess.

At least the song is short and most of it is composed of the chorus. I'd also like to point out that the musical bridge between the penultimate chorus and the final chorus is just as lovely and perfect as the chorus. So if you ignore the dog poop parts, it's really the perfect pop song.

Grade: A-.

Videodrones: Questions by Trent Reznor

Is this a song? I guess it's not really a song. It's off the Lost Highway soundtrack so it can be forgiven for not being a song. Also it's by Trent Reznor for a David Lynch movie so you're going to get what you're going to get, no matter what you just ordered from the menu. This "song" sounds like a guy masturbating in a canyon while reassuring his penis that everything is going to work out just fine right before something apocalyptic happens. I don't know what that thing is but you can tell by the music at the end that the guy's orgasm didn't really go as planned.

Grade: D.

* * * * * * * * * *

Letters to Me!

I didn't get any letters this week, you slackers! But I did have this Twitter exchange with Tom King:

That's all for this week, you jerks! Later!