If I remember correctly (which I don't always), Kurt Vonnegut said something, somewhere, about being interested in all the characters of stories. Maybe Breakfast of Champions says something about this. I don't know. It's been a long while since I've read it. And this isn't about a Kurt Vonnegut book anyway. But it's smart of me to begin by hinting that I've read loads of Kurt Vonnegut, right?! Maybe it's smarter not to even hint about it: I've read all of Vonnegut's books. I even understood like half of them.

The point I was getting at was how stories which tell the tale of a protagonist at the expense of all the people in the background whose lives are harmed or complicated or uplifted by the protagonist's actions are shallow at best. I have never been able to enjoy action-packed blockbusters where the characters the camera follows live through the huge natural disaster while thousands of others die. Am I not supposed to care about any of the other casualties? Am I supposed to feel uplifted at the end that The Rock lived? I guess I am supposed to but I never actually am.

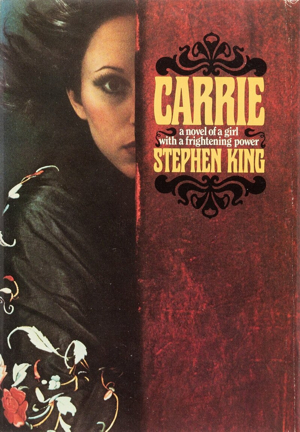

What this has to do with Carrie is that Stephen King's book isn't about a girl with telekinetic powers. It's about a town and the people who drove Carrie to do what she did and the people who wanted to help but didn't do enough and the bullies behind it all as well (always bullies in a King novel. He, for one, knows who the true antagonists of the world are. Is it Pennywise? Or is it really Henry Bowers?).

King's first novel is surprisingly more postmodern than I'd remembered (I mean, I first read it when I was 15. What did I know of postmodern?! Hell, I'm 50 now and what do I know of postmodern?!). The story is told across a variety of texts: books written after the event, transcripts of commissions trying to get to the bottom of it, books written by Carrie's peers, AP news stories. We don't just see the events unfold from Carrie's point of view. We practically see the entire town's point of view.

My favorite bit about King's style is how he somehow learned early as an author that withholding information from the reader was hack writing. I've read a lot of comic books through the years and the worst thing a writer can do is have some unnamed nemesis, allowing characters to see who it is by showing the back of the head on panel while the hero croaks, "You!", but never letting the reader know. Expecting that the reader's need to find out the answer is what will keep the reader intrigued. They don't realize that giving answers is more satisfying to the reader and giving an answer just expands the questions in the reader's mind. That keeps the reader engaged. King somehow realized this with his first novel. It's not a third of the way through the book and King has already mentioned what happened to the town on the night of prom. He's mentioned the death count. He often ends some section of story through a character's point of view with the ending summation about how they have less than two weeks to live. It's pure chaos! King's just all, "Here! You want to know how it ends? Badly! Really badly!" And then he expects—he somehow knows—that this will just keep the reader further engaged, more excited to see how Carrie turns the town into a smoldering ruin.

Oh yeah! The characters! King treats nearly all the characters that interact with Carrie in nearly any way, no matter how miniscule, as fully formed people. The respect he shows to every character in this book deserves a grand metaphor that I can't come up with. Is the book about Carrie? Yes. Is it about Sue Snell? Yes. Is it about Tommy? Yes. Billy? Yes. Chris? Yes. Momma? Yes. Teddy Duchamp? Well, no, but it was surprising to see that name! I think King just liked the name so much he used it again later for "The Body." The book is simply about all of them in a much bigger way than most books with a cast of characters allows the plot and themes to be about all of the characters. Carrie should have overshadowed everybody in this book. That she didn't just exposes, so early in his career, King's mastery of storytelling.

Being King's first novel, it suffers from all the weird King crap that all of his future novels will suffer from! I'm not here to write an essay on King's flaws. I mean, his flaws are partly what made him so popular. He says and does things in ways that no other author (or editor! Who is the champion editor that kept all that slack in King's writing leash?!) would do. Because they're grossly expressed. Or weirdly stated. Or seriously off-putting. I've already returned my ebook to the Multnomah County Library so I can't go back to find examples. But there are things like an article about people who knew Tommy and how, in a parenthetical reference, King writes, "A lot of people referred to him as a good shit." But not that! It was worded really strangely. I wish I'd kept the exact quote because it's such a weird sounding bit of slang that it may have worked fine with one person having said it but saying "a lot of people" said it just made me roll my eyes in the way that I love to roll my eyes when King is making up some cool slang. Maybe it was slang in use in Maine in the 70s but if so, I don't trust Mainers.

The book might also have been about menstruation and how menstruation is not only a sign of fertility and the beginning of life but also, starkly, a sign of the end of or loss of life when considered from the view of somebody miscarrying. Miss Carry ing? is that a thing? No, you know what, never mind. This review is done!

The point I was getting at was how stories which tell the tale of a protagonist at the expense of all the people in the background whose lives are harmed or complicated or uplifted by the protagonist's actions are shallow at best. I have never been able to enjoy action-packed blockbusters where the characters the camera follows live through the huge natural disaster while thousands of others die. Am I not supposed to care about any of the other casualties? Am I supposed to feel uplifted at the end that The Rock lived? I guess I am supposed to but I never actually am.

What this has to do with Carrie is that Stephen King's book isn't about a girl with telekinetic powers. It's about a town and the people who drove Carrie to do what she did and the people who wanted to help but didn't do enough and the bullies behind it all as well (always bullies in a King novel. He, for one, knows who the true antagonists of the world are. Is it Pennywise? Or is it really Henry Bowers?).

King's first novel is surprisingly more postmodern than I'd remembered (I mean, I first read it when I was 15. What did I know of postmodern?! Hell, I'm 50 now and what do I know of postmodern?!). The story is told across a variety of texts: books written after the event, transcripts of commissions trying to get to the bottom of it, books written by Carrie's peers, AP news stories. We don't just see the events unfold from Carrie's point of view. We practically see the entire town's point of view.

My favorite bit about King's style is how he somehow learned early as an author that withholding information from the reader was hack writing. I've read a lot of comic books through the years and the worst thing a writer can do is have some unnamed nemesis, allowing characters to see who it is by showing the back of the head on panel while the hero croaks, "You!", but never letting the reader know. Expecting that the reader's need to find out the answer is what will keep the reader intrigued. They don't realize that giving answers is more satisfying to the reader and giving an answer just expands the questions in the reader's mind. That keeps the reader engaged. King somehow realized this with his first novel. It's not a third of the way through the book and King has already mentioned what happened to the town on the night of prom. He's mentioned the death count. He often ends some section of story through a character's point of view with the ending summation about how they have less than two weeks to live. It's pure chaos! King's just all, "Here! You want to know how it ends? Badly! Really badly!" And then he expects—he somehow knows—that this will just keep the reader further engaged, more excited to see how Carrie turns the town into a smoldering ruin.

Oh yeah! The characters! King treats nearly all the characters that interact with Carrie in nearly any way, no matter how miniscule, as fully formed people. The respect he shows to every character in this book deserves a grand metaphor that I can't come up with. Is the book about Carrie? Yes. Is it about Sue Snell? Yes. Is it about Tommy? Yes. Billy? Yes. Chris? Yes. Momma? Yes. Teddy Duchamp? Well, no, but it was surprising to see that name! I think King just liked the name so much he used it again later for "The Body." The book is simply about all of them in a much bigger way than most books with a cast of characters allows the plot and themes to be about all of the characters. Carrie should have overshadowed everybody in this book. That she didn't just exposes, so early in his career, King's mastery of storytelling.

Being King's first novel, it suffers from all the weird King crap that all of his future novels will suffer from! I'm not here to write an essay on King's flaws. I mean, his flaws are partly what made him so popular. He says and does things in ways that no other author (or editor! Who is the champion editor that kept all that slack in King's writing leash?!) would do. Because they're grossly expressed. Or weirdly stated. Or seriously off-putting. I've already returned my ebook to the Multnomah County Library so I can't go back to find examples. But there are things like an article about people who knew Tommy and how, in a parenthetical reference, King writes, "A lot of people referred to him as a good shit." But not that! It was worded really strangely. I wish I'd kept the exact quote because it's such a weird sounding bit of slang that it may have worked fine with one person having said it but saying "a lot of people" said it just made me roll my eyes in the way that I love to roll my eyes when King is making up some cool slang. Maybe it was slang in use in Maine in the 70s but if so, I don't trust Mainers.

The book might also have been about menstruation and how menstruation is not only a sign of fertility and the beginning of life but also, starkly, a sign of the end of or loss of life when considered from the view of somebody miscarrying. Miss Carry ing? is that a thing? No, you know what, never mind. This review is done!

P.S. This part of the review isn't in my original review I posted on Goodreads because I just thought of it thanks to my lame joke at the end. Could this book be about Carrie's mother miscarrying Carrie? Is the book about her mother's hopes and dreams of her child that end in a torrent of blood and misery and grief? The evidence for this isn't actually in the book. The evidence for this is in Danielewski's House of Leaves which might possibly be telling the same kind of story: Pelafina loses Johnny Truant at birth and his entire life is made up by her while in The Whalestoe asylum. He was her little boy that she lost. He was truant. The five and a half minute hallway that his sister Poe sings about, the choking of Johnny by his mother in the foyer of their home (you know, the entrance/exit to the womb), are all metaphors for strangling during birth. At the end, Johnny remembers his mother's final words before letting him go. But not knowing Latin, he hears them phonetically: Etch a Pooh Air. Behold, a boy. Did King beat Danielewski to the punch with the mother's delusional life dream of her child lost at birth (or by miscarriage)?! Um, probably! I'm smart!

No comments:

Post a Comment