E!TACT! #14

Dark Knights Rising: The Wild Hunt #1, Deadman #4, Michael Cray #5, Suicide Squad #35, Detective Comics #974, Justice League of America #24, Sideways #1, Action Comics #997, Grunion Guy's Musical Corner of Music Reviews, and Zero Letters to Me!

By Grunion Guy

Thanks to my stupid quarter anniversary issue, I've fallen way behind on my comic book reading! I could probably blame other things like video games and my absent father but I don't want to sound like a whining loser. I want to sound tough and industrious! "I was too busy writing something else to write my opinions on the shittiest of pop culture's offerings!" That was a quote exemplifying the industrious part of the illusion. Here's the quote showing off the tough side: "Fuck everybody! I'll punch them square in their jaws!" Whoa! I wouldn't mess with me!

This would normally be the newsletter where I read eighteen comics in one sitting and offer up a dick joke or two for each book. But the top book on my list is Dark Knights Rising: The Wild Hunt. How the fuck am I not going to write an in-depth explication of a book co-authored by Scott Snyder and Grant Morrison?! Now the bulk of this newsletter will be taken up by this bullshit and I won't be any closer to shortening my stack of unread filth and disappointment! Fuck you, Grant Morrison! I'll punch you square in the jaw!

Dark Knights Rising: The Wild Hunt #1

By Snyder, Morrison, Tynion IV, Williamson, Porter, Jimenez, Mahnke, Mendoza, Hi-Fi, Sanchez, and Quintana

The story begins with Detective Chimp quoting Socrates: "The unexamined life is not worth living." I can see why some people would throw roses into this statement's face but I have a problem with it, in the context of when it was supposedly spoken. If the choice is exile or death, why can't I choose exile without looking like I sold out on all of my principles? Can't I still examine things in exile? Surely the boys I corrupted could check out books for me from the library and bring them to my cave where I spend fifteen hours a day masturbating. Even if they couldn't, isn't masturbating fifteen hours a day better than death? Don't answer that, you prudes! It totally is.

Of course, I'm ignoring the fact that Socrates believed in an afterlife. I suppose if I was positive there was another world after this one, I wouldn't have to wait to be sentenced to death for corrupting the Tumblr youth with my problematic and sexy ideas. These wrists would be gushing blood as I ran about the neighborhood telling the children, "Death is easy! Life is hard! And I'm pretty fucking lazy, so, you know." The afterlife couldn't be any worse than this farce of a capitalist democracy in which I indulge in every creature comfort but still drown in existential angst because I have to pay rent and cook my own meals, could it? Unless the afterlife is worse than a farce of a capitalist democracy and is a farce of a fascist military state! Oh man. Now I'm even more afraid to die than I was five minutes ago (where I was at my peak fear of death. In five minutes, it will probably be a new peak fear of death. That trend should continue right up until I think, "What is that nois....").

Back to Detective Chimp, I don't think Socrates was saying life wasn't worth living unless you were a detective examining crime scenes. I think Dr. Chimp is being a bit flippant about the quote. But then this is Snyder so the quote will probably prove to be important later which is why it had to be uttered now as a non sequitur. I mean, I guess it's not a non sequitur since it's simply the first thing the chimp utters. It's actually the beginning of the story because Detective Chimp is investigating who said the quote and why he can't remember who said it. If only he had access to Wikipedia, this comic book would be over! But chimps aren't allowed to use the computers in the library because they would spend fifteen hours a day masturbating there.

Detective Chimp remembers how he escaped from the circus only to team up with Rex the Wonder Dog. That means I need to reassess who the main writer on this book was. Must be Morrison! You know, because an old comic book character has now been resurrected. Also because I'm finding the story interesting and entertaining!

Rex leads Detective Chimp to the Fountain of Youth which also happens to be the Fountain of Smarts. As soon as Detective Chimp learns to think past the constant rage that makes him want to tear the faces off all the patronizing furless apes he's ever met, he discovers that all cruelty stems from a lack of imagination. I don't know. The Inquisition came up with some pretty imaginative ways to be cruel. He equates a lack of imagination with "anti-music!" That totally sounds like Morrison. I hope that doesn't mean that's the end of his section because then I'm left with reading shit by James Tynion IV and Joshua Williamson. I'm bored just imagining the anti-music those jerks came up with.

It's also possible Morrison got a co-writing credit simply because this story is using so much of his Multiversity shit. I don't know everything! More like I know everything minus X where X is a pretty low number. Unless not knowing things is what makes a person smart! No, no. That makes a person wise! So knowing things that I know I don't know makes me the wisest person of them all. Is that how that works? You know I'm wise because I pretend I'm not? Cause I totally am not wise. Way dumb, me! I mean, am I smart because I know stuff or wise because I don't know stuff? Can nobody ever actually have an 18 Intelligence and 18 Wisdom? Fucking Dungeons & Dragons. Lied to me yet again!

This would normally be the newsletter where I read eighteen comics in one sitting and offer up a dick joke or two for each book. But the top book on my list is Dark Knights Rising: The Wild Hunt. How the fuck am I not going to write an in-depth explication of a book co-authored by Scott Snyder and Grant Morrison?! Now the bulk of this newsletter will be taken up by this bullshit and I won't be any closer to shortening my stack of unread filth and disappointment! Fuck you, Grant Morrison! I'll punch you square in the jaw!

Dark Knights Rising: The Wild Hunt #1

By Snyder, Morrison, Tynion IV, Williamson, Porter, Jimenez, Mahnke, Mendoza, Hi-Fi, Sanchez, and Quintana

The story begins with Detective Chimp quoting Socrates: "The unexamined life is not worth living." I can see why some people would throw roses into this statement's face but I have a problem with it, in the context of when it was supposedly spoken. If the choice is exile or death, why can't I choose exile without looking like I sold out on all of my principles? Can't I still examine things in exile? Surely the boys I corrupted could check out books for me from the library and bring them to my cave where I spend fifteen hours a day masturbating. Even if they couldn't, isn't masturbating fifteen hours a day better than death? Don't answer that, you prudes! It totally is.

Of course, I'm ignoring the fact that Socrates believed in an afterlife. I suppose if I was positive there was another world after this one, I wouldn't have to wait to be sentenced to death for corrupting the Tumblr youth with my problematic and sexy ideas. These wrists would be gushing blood as I ran about the neighborhood telling the children, "Death is easy! Life is hard! And I'm pretty fucking lazy, so, you know." The afterlife couldn't be any worse than this farce of a capitalist democracy in which I indulge in every creature comfort but still drown in existential angst because I have to pay rent and cook my own meals, could it? Unless the afterlife is worse than a farce of a capitalist democracy and is a farce of a fascist military state! Oh man. Now I'm even more afraid to die than I was five minutes ago (where I was at my peak fear of death. In five minutes, it will probably be a new peak fear of death. That trend should continue right up until I think, "What is that nois....").

Back to Detective Chimp, I don't think Socrates was saying life wasn't worth living unless you were a detective examining crime scenes. I think Dr. Chimp is being a bit flippant about the quote. But then this is Snyder so the quote will probably prove to be important later which is why it had to be uttered now as a non sequitur. I mean, I guess it's not a non sequitur since it's simply the first thing the chimp utters. It's actually the beginning of the story because Detective Chimp is investigating who said the quote and why he can't remember who said it. If only he had access to Wikipedia, this comic book would be over! But chimps aren't allowed to use the computers in the library because they would spend fifteen hours a day masturbating there.

Detective Chimp remembers how he escaped from the circus only to team up with Rex the Wonder Dog. That means I need to reassess who the main writer on this book was. Must be Morrison! You know, because an old comic book character has now been resurrected. Also because I'm finding the story interesting and entertaining!

Rex leads Detective Chimp to the Fountain of Youth which also happens to be the Fountain of Smarts. As soon as Detective Chimp learns to think past the constant rage that makes him want to tear the faces off all the patronizing furless apes he's ever met, he discovers that all cruelty stems from a lack of imagination. I don't know. The Inquisition came up with some pretty imaginative ways to be cruel. He equates a lack of imagination with "anti-music!" That totally sounds like Morrison. I hope that doesn't mean that's the end of his section because then I'm left with reading shit by James Tynion IV and Joshua Williamson. I'm bored just imagining the anti-music those jerks came up with.

It's also possible Morrison got a co-writing credit simply because this story is using so much of his Multiversity shit. I don't know everything! More like I know everything minus X where X is a pretty low number. Unless not knowing things is what makes a person smart! No, no. That makes a person wise! So knowing things that I know I don't know makes me the wisest person of them all. Is that how that works? You know I'm wise because I pretend I'm not? Cause I totally am not wise. Way dumb, me! I mean, am I smart because I know stuff or wise because I don't know stuff? Can nobody ever actually have an 18 Intelligence and 18 Wisdom? Fucking Dungeons & Dragons. Lied to me yet again!

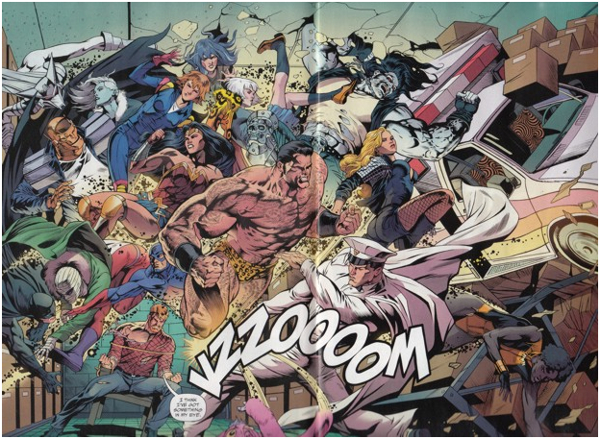

This would probably be the new blog header if I cared about updating the blog.

T.O. Morrow has determined that something cosmic is happening because the immutable laws of physics are changing. To demonstrate this, he uses the most immutable law of physics around: the boiling point of water!

Excuse me while I slam my face through my office window three or four times. Okay, actually just once. I need more windows in here.

Since none of my readers are conservatives, I don't need to explain why I just destroyed my beautiful face out of frustration. Let's just move on.

Detective Chimp has been trying to guide Flash, Raven, and Cyborg to the Hall of Heroes. The team travels in the Ultima Thule while being chased down by all of the Dark Knights. They call themselves The Wild Hunt now. Did they call themselves that prior to this issue? And did I just forget that Flash, Cyborg, and Raven wound up on the Ultima Thule? I guess I must have since this Metal shit has been going on for approximately eight years now.

The Wild Hunt's ship (The Carrier! Did I miss when they stole that from Stormwatch?) runs on a baby universe. Like Rick's ship! The Flash's plan is to free the baby universe which should stop The Carrier and also fix the multiverse with its positive baby universe energy. Also it will allow DC to make a completely new comic book line, hopefully designed by Grant Morrison.

Excuse me while I slam my face through my office window three or four times. Okay, actually just once. I need more windows in here.

Since none of my readers are conservatives, I don't need to explain why I just destroyed my beautiful face out of frustration. Let's just move on.

Detective Chimp has been trying to guide Flash, Raven, and Cyborg to the Hall of Heroes. The team travels in the Ultima Thule while being chased down by all of the Dark Knights. They call themselves The Wild Hunt now. Did they call themselves that prior to this issue? And did I just forget that Flash, Cyborg, and Raven wound up on the Ultima Thule? I guess I must have since this Metal shit has been going on for approximately eight years now.

The Wild Hunt's ship (The Carrier! Did I miss when they stole that from Stormwatch?) runs on a baby universe. Like Rick's ship! The Flash's plan is to free the baby universe which should stop The Carrier and also fix the multiverse with its positive baby universe energy. Also it will allow DC to make a completely new comic book line, hopefully designed by Grant Morrison.

This is why so many writers choose to have Flash fight other speedsters and/or time travelers. Because every conflict would end like this. The problem with writers using that solution is that these three panels are far more interesting and entertaining than a five issue story arc where The Flash can't beat somebody because they're faster than he is right up until the moment The Flash believes he can run faster and thus does and wins.

The only problem with The Flash doing the thing he thinks will save the day is that his doing that thing was part of the plan of the Bat-Joker. In other words, every single thing that has happened was part of a plan that would never actually work because the calculation contains about seventeen million variables. So, in traditional comic book fashion, it makes me happy one moment only to shit all over my happiness, lap up the shit and my happiness, digest it so that my happiness is now intrinsically part of its shit, and then shit it all over me once again.

Flash, Raven, and Cyborg winding up as a team and boarding the Ultima Thule and heading to the Hall of Heroes being directed by Detective Chimp and other super scientists while also being infected by Dark Baby Universe missiles (along with all the other things that had to happen along the way) was the main part of the plan to destroy the Multiverse. I guess I just have to stop thinking that superheroes are smart and just resign myself to the realization that they're all easily manipulated fools. Maybe it's more believable because the bad guys are twenty-eight Batmans.

The end of everything almost happens. But just almost because there is still one more issue of Metal to sell for loads of cash. Coming through to save the day are the super chimps from Earth-53. That's right! You read that correctly! A 53rd EARTH! What an incredible twist! Also that it's the Earth where everybody is a monkey. Also also, they're going to save the multiverse. Ha ha! How funny! A bunch of monkeys saving the day!

The Wild Hunt #1 Rating: It was pretty good! The best Metal book yet! Mostly because it was so closely tied to Multiversity and second mostly because it starred Detective Chimp.

Deadman #4

By Neal Adams

Deadman discovers that he was killed by the League of Assassins in retaliation for his parents killing a bunch of Yeti guarding Nanda Parbat. I think there's more to it than that, like how they were searching for their son Aaron who was given to the League as payment for healing Deadman's mother. Unless I got some of that wrong because my memory of comic books I hated isn't the best.

So is Deadman satisfied with his journey of self-discovery yet? Hopefully not because I still haven't found out why Commissioner Gordon was inspecting Japanese nuclear plants! I'm beginning to think that Neal Adams is just hoping that I'd forget about that part. But Neal Adams doesn't know how stubborn and bitter and hateful I can be.

Boston reveals to the Spectre that his father was lying. Well great! That really means two more issues of this shit! I actually had myself convinced that it was going to end early. What a sap!

Apparently Ra's wants Boston Brand back in Nanda Parbat for some important League of Assassins reasons. There's some other confusing stuff about Aaron Brand that I don't think matters but it probably will matter. Which is disappointing because it's terrible and confusing. I hate this book. Why do I now own four issues of it?

Deadman #4 Rating: Possibly the worst comic book I've ever read after Deadman #1 and Deadman #2. I think Deadman #3 wasn't quite as bad as the others.

Michael Cray #5

By Hill, Ellis, Harris, Vines, Owens, and Kelly

This issue begins with a bunch of New Zealanders sacrificing a woman to Aquaman. She's probably a virgin because that's always the scam. You get a bunch of zealots to proclaim that their god will only be satisfied by a virgin sacrifice so that all the women of the village suddenly loosen their pants-strings.

Male Elder (with throbbing boner) speaking to throng: "Looks like we're going to have a poor harvest, wouldn't you agree, Bob?"

Male Elder named Bob (also with throbbing boner): "Yep. I think we might need to sacrifice five or six virgins this year."

Male Elder gazing at lush farm fields (with boner, of course): "Well, we might do get by with only one if we're lucky, right?"

All the women: "Oh, um, we totally fucked already. Maybe we can just try our luck with hard work and scientific advancements in the agricultural sciences?"

Male Elder standing with hands on his hips and thrusting his pants-tented boner toward the crowd: "Seems awful risky. Nope, I think we need some virgins. And y'all keep saying you've fucked but there's only one way to know for sure."

All the women: *collective sigh*

Male Elder named Bob: "Now who wants to get their name crossed off the list first? Remember, anal counts as doubly devirginizing!"

All the male virgins planning their next Dungeons & Dragons campaigns: "Fucking sluts! Why don't they ever fuck us?! We can't wait to become powerful village politicians running on conservative and traditional values so that our community never evolves and grows and we get our turn to get laid thanks to terrible historical power dynamics!"

The non-virgin male: "Or maybe you could, I don't know, treat the women like actual people?"

All the male virgins: "And risk them getting their hands on the reigns of power? What if they decide 'virgin' can also mean male?! They'll do it, you know! They won't make things better! They'll just make things as bad as we've made things but for us! Don't trust them!"

Non-virgin male eating pussy: "Garble blargle...oh, um, excuse me. Did you say something?"

Flash, Raven, and Cyborg winding up as a team and boarding the Ultima Thule and heading to the Hall of Heroes being directed by Detective Chimp and other super scientists while also being infected by Dark Baby Universe missiles (along with all the other things that had to happen along the way) was the main part of the plan to destroy the Multiverse. I guess I just have to stop thinking that superheroes are smart and just resign myself to the realization that they're all easily manipulated fools. Maybe it's more believable because the bad guys are twenty-eight Batmans.

The end of everything almost happens. But just almost because there is still one more issue of Metal to sell for loads of cash. Coming through to save the day are the super chimps from Earth-53. That's right! You read that correctly! A 53rd EARTH! What an incredible twist! Also that it's the Earth where everybody is a monkey. Also also, they're going to save the multiverse. Ha ha! How funny! A bunch of monkeys saving the day!

The Wild Hunt #1 Rating: It was pretty good! The best Metal book yet! Mostly because it was so closely tied to Multiversity and second mostly because it starred Detective Chimp.

Deadman #4

By Neal Adams

Deadman discovers that he was killed by the League of Assassins in retaliation for his parents killing a bunch of Yeti guarding Nanda Parbat. I think there's more to it than that, like how they were searching for their son Aaron who was given to the League as payment for healing Deadman's mother. Unless I got some of that wrong because my memory of comic books I hated isn't the best.

So is Deadman satisfied with his journey of self-discovery yet? Hopefully not because I still haven't found out why Commissioner Gordon was inspecting Japanese nuclear plants! I'm beginning to think that Neal Adams is just hoping that I'd forget about that part. But Neal Adams doesn't know how stubborn and bitter and hateful I can be.

Boston reveals to the Spectre that his father was lying. Well great! That really means two more issues of this shit! I actually had myself convinced that it was going to end early. What a sap!

Apparently Ra's wants Boston Brand back in Nanda Parbat for some important League of Assassins reasons. There's some other confusing stuff about Aaron Brand that I don't think matters but it probably will matter. Which is disappointing because it's terrible and confusing. I hate this book. Why do I now own four issues of it?

Deadman #4 Rating: Possibly the worst comic book I've ever read after Deadman #1 and Deadman #2. I think Deadman #3 wasn't quite as bad as the others.

Michael Cray #5

By Hill, Ellis, Harris, Vines, Owens, and Kelly

This issue begins with a bunch of New Zealanders sacrificing a woman to Aquaman. She's probably a virgin because that's always the scam. You get a bunch of zealots to proclaim that their god will only be satisfied by a virgin sacrifice so that all the women of the village suddenly loosen their pants-strings.

Male Elder (with throbbing boner) speaking to throng: "Looks like we're going to have a poor harvest, wouldn't you agree, Bob?"

Male Elder named Bob (also with throbbing boner): "Yep. I think we might need to sacrifice five or six virgins this year."

Male Elder gazing at lush farm fields (with boner, of course): "Well, we might do get by with only one if we're lucky, right?"

All the women: "Oh, um, we totally fucked already. Maybe we can just try our luck with hard work and scientific advancements in the agricultural sciences?"

Male Elder standing with hands on his hips and thrusting his pants-tented boner toward the crowd: "Seems awful risky. Nope, I think we need some virgins. And y'all keep saying you've fucked but there's only one way to know for sure."

All the women: *collective sigh*

Male Elder named Bob: "Now who wants to get their name crossed off the list first? Remember, anal counts as doubly devirginizing!"

All the male virgins planning their next Dungeons & Dragons campaigns: "Fucking sluts! Why don't they ever fuck us?! We can't wait to become powerful village politicians running on conservative and traditional values so that our community never evolves and grows and we get our turn to get laid thanks to terrible historical power dynamics!"

The non-virgin male: "Or maybe you could, I don't know, treat the women like actual people?"

All the male virgins: "And risk them getting their hands on the reigns of power? What if they decide 'virgin' can also mean male?! They'll do it, you know! They won't make things better! They'll just make things as bad as we've made things but for us! Don't trust them!"

Non-virgin male eating pussy: "Garble blargle...oh, um, excuse me. Did you say something?"

"'Why her?' She knew this dick wasn't going to suck itself."

I wrote my vignette using the "elder" characters before I got to the part with that elder character because I'm a Grandmaster Comic Book Reader. Although if I were really serious about being a Grandmaster Comic Book Reader, I should probably better remember the comic books I've read. Although it's not like I claim to be a Grandmaster Comic Book Historian! I'm just good at reading them and guessing where they're headed and pulling out my dick and pissing all over them.

And don't think you can picture my dick in your imagination just because I mentioned it, you pervert! That was just a metaphorical dick standing in for the abuse I heap upon the comic books I waste my money on!

Aquaman doesn't die yet. We'll get to that next issue. And believe me, I'll be buying five copies of it! No wait. Just four. Oh shit. This book is $3.99? Maybe I'll just read it off the rack.

Michael Cray #5 Rating: This book felt like it was going downhill for a few issues (which means most of the issues after I lost my "Green Arrow is going to die!" boner). But I really liked this issue for some reason! "Some reason" is the best you'll get out of me. Other comic book reviewers would be all, "The art was particularly tasty in the way it showed the emotion inherent in the words that were written so well. Plus the letterer did his job so I was able to read it." Then they throw a bunch of dick sucking superlatives across a few closing sentences and rate the thing 9.8 out of 10. But not me! I don't know why I like or dislike things! So I don't bother trying to come up with reasons. I just read the book and then glance at my crotch to see if I liked it or not.

Suicide Squad #35

By Williams, Pansica, Ferreira, and Lucas

Ugh. Williams is back? Not that what's-his-name from the last couple of issues was any better. I wonder how many unread issues of this comic book are being purchased by Harley Quinn fans to prop up the illusion that it's a successful book?

The cover of this issue says, "And their dead shall come for them!" So that means, um, Hack will be back? She's the only member who has died. I don't even consider her an actual member. She wasn't a prisoner. She was just kidnapped from another country's prison and forced to work on the team because Amanda Waller gets to write reality. But Hack put up with it because she wanted to fuck Harley Quinn.

By the way! (Is that a complete sentence? Does this parenthetical reference work? What are grammar?) Is that how reality works? If somebody is in prison in one country and they somehow find themselves in another country through a ridiculous plot device, do they have to be placed in prison in the new country? My guess is that it doesn't work that way because it doesn't even work when somebody is a child rapist in America and they move to France to suddenly not be a child rapist. Or if somebody is a rapist in Sweden, they can move to a broom closet in the basement of an Ecuadorian embassy in London to remain "free."

Anyway, Hack has come back because — as I've noted before — nobody actually dies in the Suicide Squad. Everybody gets to come back. Except Light. Or was it Lime? Who can tell?

Suicide Squad #35 Rating: This book is terrible. I hated myself for buying it. Then I hated myself more for reading it. Then I realized I can't actually hate myself any more than I do when I'm not reading it. So why not keep reading it? Now I hate myself for coming to that conclusion. Why doesn't my mother love me?!

Detective Comics #974

By Tynion IV, Briones, and Passalaqua

This issue is called Knights Fall because Batman fans can't get away from witty writers who won't stop referencing past story arcs to score easy fan points while also showcasing how "night" and "knight" are homonyms that can be cleverly manipulated in the Batman franchise. So immediately after reading the title "Knights Fall," I found myself foaming at the mouth and orgasming involuntarily. If I hadn't already had loads and loads of sex with women that would probably mean I'm not a virgin anymore, right? Although, just to clarify for hypothetical reasons, would I say my first time was with James Tynion IV or Detective Comics?

Batwoman has killed Clayface and now all the Bat-people are angry at her. Batman is all, "You killed a person that was going to kill hundreds of people! How could you?! Now you have a death on your hands when technically, if you hadn't killed him, you wouldn't have hundreds of deaths on your hands! Haven't you read my book, Five Million Excuses For Why Somebody's Death Wasn't Technically My Fault?!" Then Batwoman is all, "I did what any soldier or cop would have been lauded for doing!" And Tim is all, "Fuck soldiers and cops! We're better than soldiers and cops! They're scared sheep who think violence is always the answer!" Batman sort of coughs and adjusts his tie and looks askance at that. Then Cass is all, "Look at me crying, readers! Doesn't your heart just break for me! Boo hoo!"

It's really all quite dramatic! I'm quivering with whatever emotion it is that other people can feel that makes them quiver!

Azrael and Batwing decide to tell Batman sometimes killing works so they get put on leave alongside Batwoman. As if Batman has the power to stop a vigilante from vigilanting. Who died and made him king of Gotham? Oh, that's right! Thomas and Martha!

Thankfully, Tim Drake was visited by a morally corrupt version of himself from the future which enables him to struggle with the actions he wants to take. If he didn't already know he's heading down a dark path, where would the immediate conflict come from?! Boy how I love time travel and alternate timeline story arcs! They make it so much easier to write dramatic character moments! I might miss the subtleties of seeing Tim Drake veer down a darker path due to his present experiences if I hadn't already been told about the dark path! Thanks for telling me how I should feel about each character and their decisions, James! I hate the feeling of ambiguity I'm left with after reading works by great writers.

Meanwhile, Ulysses is working with Brother Eye to bring about the worst DC future possible. I mean, it's not actually worse than the canonical version of DC's future. But I guess it's bad because Tim Drake becomes a menace and a killer? We already knew he would become Harvest anyway so how is this any different?!

Detective Comics #974 Rating: Should comic books only be reviewed by people who enjoy that particular comic book? Does it really mean anything if I say I hate Detective Comics written by James Tynion IV? That's what everybody expects! I suppose it only means something if I say I like it and somebody who loves the series says they hated it. I don't mean the same issue! I just mean...oh, forget it! You probably know what I mean. And if you don't, I can't blame myself for your lack of comprehension. Especially if you've made it this far into the newsletter. You know my writing has no clarity!

Justice League of America #24

By Orlando, Edwards, Henriques, Hi-fi

The Justice League of America saves some day from something terrible happening. Promethea makes an appearance to remind me that I still need to read that series. And then after everything is settled and peace has been made and there's nothing left for anybody to do, Batman shows up to be the leader again. Christ. He's like that one member of the installation crew who only shows up after the truck has been unloaded and then disappears once again when you turn your back, leaving only a whiff of meth smoke in his wake.

Justice League of America #24 Rating: Well, it had Lobo in it. So it was the best comic book I've read this week!

Sideways #1

By Rocafort, DiDio, Jordan, and Brown

You can tell these new Metal-inspired books are crap because they give the artists top billing. I'd say it's an insult to the readership as well, assuming that they believe art tops writing but as we all know, that's mostly true. It must be or else we'd all have our dicks stuck balls deep into The Familiar Part May 5th by the guy who wrote the book about a house. And I meant our metaphorical dicks and our metaphorical balls. Later, I'll say something about our metaphorical vaginas so that nobody feels left out and so that hermaphrodites feel doubly left in.

My Four Hermaphroditic Readers: "I really identified with both of those metaphors while ruining my underpants in two ways!"

Me: "I really don't know anything about hermaphrodites!"

My Tumblr Readers, scrutinizing every word carefully: "They haven't made any semantic mistakes that we can call them out on but my gut tells me they're erasing the transgender community!"

I should be happy that they put Kenneth Rocafort's name first. It saves me time realizing that I'm not interested in this comic book. Yes, I purchased it. But I only did that because I only had about four comics in my pull box that week. So my adult reasoning went something like this: "I'm an idiot with three extra dollars in my stupid pocket! Let me ruin future me's day when he realizes past me (currently present me!) purchased this awful book for him to read! Ha ha! In your face, fatty!"

And don't think you can picture my dick in your imagination just because I mentioned it, you pervert! That was just a metaphorical dick standing in for the abuse I heap upon the comic books I waste my money on!

Aquaman doesn't die yet. We'll get to that next issue. And believe me, I'll be buying five copies of it! No wait. Just four. Oh shit. This book is $3.99? Maybe I'll just read it off the rack.

Michael Cray #5 Rating: This book felt like it was going downhill for a few issues (which means most of the issues after I lost my "Green Arrow is going to die!" boner). But I really liked this issue for some reason! "Some reason" is the best you'll get out of me. Other comic book reviewers would be all, "The art was particularly tasty in the way it showed the emotion inherent in the words that were written so well. Plus the letterer did his job so I was able to read it." Then they throw a bunch of dick sucking superlatives across a few closing sentences and rate the thing 9.8 out of 10. But not me! I don't know why I like or dislike things! So I don't bother trying to come up with reasons. I just read the book and then glance at my crotch to see if I liked it or not.

Suicide Squad #35

By Williams, Pansica, Ferreira, and Lucas

Ugh. Williams is back? Not that what's-his-name from the last couple of issues was any better. I wonder how many unread issues of this comic book are being purchased by Harley Quinn fans to prop up the illusion that it's a successful book?

The cover of this issue says, "And their dead shall come for them!" So that means, um, Hack will be back? She's the only member who has died. I don't even consider her an actual member. She wasn't a prisoner. She was just kidnapped from another country's prison and forced to work on the team because Amanda Waller gets to write reality. But Hack put up with it because she wanted to fuck Harley Quinn.

By the way! (Is that a complete sentence? Does this parenthetical reference work? What are grammar?) Is that how reality works? If somebody is in prison in one country and they somehow find themselves in another country through a ridiculous plot device, do they have to be placed in prison in the new country? My guess is that it doesn't work that way because it doesn't even work when somebody is a child rapist in America and they move to France to suddenly not be a child rapist. Or if somebody is a rapist in Sweden, they can move to a broom closet in the basement of an Ecuadorian embassy in London to remain "free."

Anyway, Hack has come back because — as I've noted before — nobody actually dies in the Suicide Squad. Everybody gets to come back. Except Light. Or was it Lime? Who can tell?

Suicide Squad #35 Rating: This book is terrible. I hated myself for buying it. Then I hated myself more for reading it. Then I realized I can't actually hate myself any more than I do when I'm not reading it. So why not keep reading it? Now I hate myself for coming to that conclusion. Why doesn't my mother love me?!

Detective Comics #974

By Tynion IV, Briones, and Passalaqua

This issue is called Knights Fall because Batman fans can't get away from witty writers who won't stop referencing past story arcs to score easy fan points while also showcasing how "night" and "knight" are homonyms that can be cleverly manipulated in the Batman franchise. So immediately after reading the title "Knights Fall," I found myself foaming at the mouth and orgasming involuntarily. If I hadn't already had loads and loads of sex with women that would probably mean I'm not a virgin anymore, right? Although, just to clarify for hypothetical reasons, would I say my first time was with James Tynion IV or Detective Comics?

Batwoman has killed Clayface and now all the Bat-people are angry at her. Batman is all, "You killed a person that was going to kill hundreds of people! How could you?! Now you have a death on your hands when technically, if you hadn't killed him, you wouldn't have hundreds of deaths on your hands! Haven't you read my book, Five Million Excuses For Why Somebody's Death Wasn't Technically My Fault?!" Then Batwoman is all, "I did what any soldier or cop would have been lauded for doing!" And Tim is all, "Fuck soldiers and cops! We're better than soldiers and cops! They're scared sheep who think violence is always the answer!" Batman sort of coughs and adjusts his tie and looks askance at that. Then Cass is all, "Look at me crying, readers! Doesn't your heart just break for me! Boo hoo!"

It's really all quite dramatic! I'm quivering with whatever emotion it is that other people can feel that makes them quiver!

Azrael and Batwing decide to tell Batman sometimes killing works so they get put on leave alongside Batwoman. As if Batman has the power to stop a vigilante from vigilanting. Who died and made him king of Gotham? Oh, that's right! Thomas and Martha!

Thankfully, Tim Drake was visited by a morally corrupt version of himself from the future which enables him to struggle with the actions he wants to take. If he didn't already know he's heading down a dark path, where would the immediate conflict come from?! Boy how I love time travel and alternate timeline story arcs! They make it so much easier to write dramatic character moments! I might miss the subtleties of seeing Tim Drake veer down a darker path due to his present experiences if I hadn't already been told about the dark path! Thanks for telling me how I should feel about each character and their decisions, James! I hate the feeling of ambiguity I'm left with after reading works by great writers.

Meanwhile, Ulysses is working with Brother Eye to bring about the worst DC future possible. I mean, it's not actually worse than the canonical version of DC's future. But I guess it's bad because Tim Drake becomes a menace and a killer? We already knew he would become Harvest anyway so how is this any different?!

Detective Comics #974 Rating: Should comic books only be reviewed by people who enjoy that particular comic book? Does it really mean anything if I say I hate Detective Comics written by James Tynion IV? That's what everybody expects! I suppose it only means something if I say I like it and somebody who loves the series says they hated it. I don't mean the same issue! I just mean...oh, forget it! You probably know what I mean. And if you don't, I can't blame myself for your lack of comprehension. Especially if you've made it this far into the newsletter. You know my writing has no clarity!

Justice League of America #24

By Orlando, Edwards, Henriques, Hi-fi

The Justice League of America saves some day from something terrible happening. Promethea makes an appearance to remind me that I still need to read that series. And then after everything is settled and peace has been made and there's nothing left for anybody to do, Batman shows up to be the leader again. Christ. He's like that one member of the installation crew who only shows up after the truck has been unloaded and then disappears once again when you turn your back, leaving only a whiff of meth smoke in his wake.

Justice League of America #24 Rating: Well, it had Lobo in it. So it was the best comic book I've read this week!

Sideways #1

By Rocafort, DiDio, Jordan, and Brown

You can tell these new Metal-inspired books are crap because they give the artists top billing. I'd say it's an insult to the readership as well, assuming that they believe art tops writing but as we all know, that's mostly true. It must be or else we'd all have our dicks stuck balls deep into The Familiar Part May 5th by the guy who wrote the book about a house. And I meant our metaphorical dicks and our metaphorical balls. Later, I'll say something about our metaphorical vaginas so that nobody feels left out and so that hermaphrodites feel doubly left in.

My Four Hermaphroditic Readers: "I really identified with both of those metaphors while ruining my underpants in two ways!"

Me: "I really don't know anything about hermaphrodites!"

My Tumblr Readers, scrutinizing every word carefully: "They haven't made any semantic mistakes that we can call them out on but my gut tells me they're erasing the transgender community!"

I should be happy that they put Kenneth Rocafort's name first. It saves me time realizing that I'm not interested in this comic book. Yes, I purchased it. But I only did that because I only had about four comics in my pull box that week. So my adult reasoning went something like this: "I'm an idiot with three extra dollars in my stupid pocket! Let me ruin future me's day when he realizes past me (currently present me!) purchased this awful book for him to read! Ha ha! In your face, fatty!"

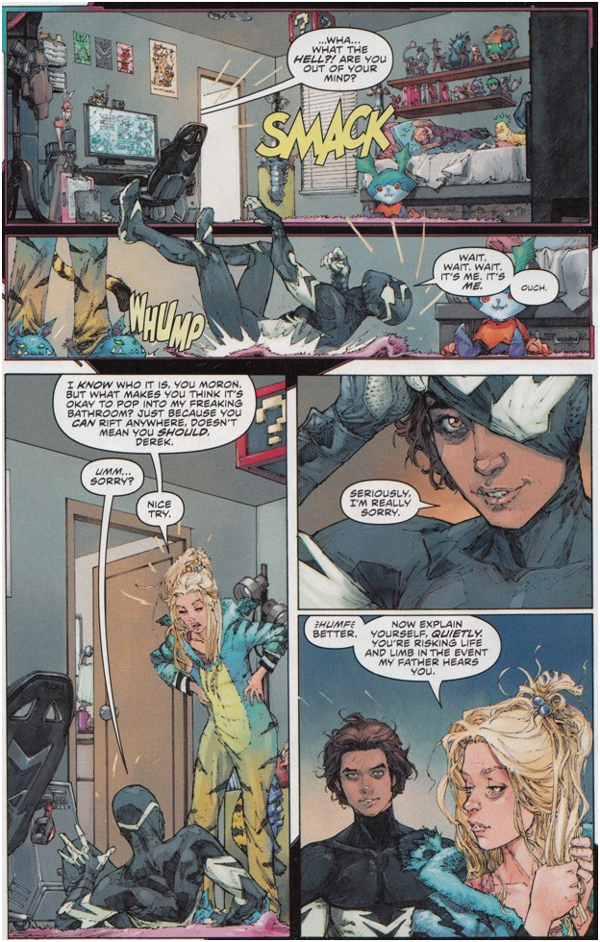

"Don't worry. My father is used to hearing me scream at myself constantly."

Sideways is a young person in young school who has young friends with young attitudes so that should get the young people reading this young comic written by a sixty year old man.

Sideways' best friend is Ernestine. She's the exact character an old person would come up with after doing a bunch of research on Tumblr if that old person were making a character to connect with the kids. She's got her own unique style that's actually just pop culture camouflage hiding whatever her true personality is. I suppose the true personality is that she loves things so much that she squeeeees. She's the person who feels they have to be the biggest fan of everything to show how perky and different they are. She also wears a tiger skin onesie to school. And just to make sure that the readers understand just how outside of "normal" societal standards she is, she has a twin sister who totally dresses like mainstream America expects teenage girls to dress! She's got the regular pants and the regular shirt and the regular half-jacket and the regular shades on her regular blonde head. She also makes sure to point out that Ernestine's outfit isn't appropriate for school. In other words, she's a Popular. And us comic book reading nerds understand that they're the bad guys!

Sideways, like The Flash, is always late. That's a hilarious character defect for somebody who can be anywhere instantaneously! I bet Dan DiDio chuckled for five minutes thinking up that character trait.

Sideways is a brown boy named Derek who was adopted by an upper middle class white couple. Didn't society agree three decades ago that this was a racist trope? Weren't white people's lust for rescuing the non-whites satiated by Diff'rent Strokes and Webster? I suppose if I wanted to be upbeat with my hot takes on old television shows, I could set forth the theory that the vivacious and culturally eccentric personalities of the young minorities helped save the white people from living boring and mediocre lives in a loveless vacuum! That was the premise of Punky Brewster and that was practically the same show minus the eternally childlike black children from the other shows.

Speaking of terrible comic book tropes that never die (which is what makes them tropes! Geez! Get a dictionary, fatty! (HEY!)), Derek seems to be a boy genius who was about to get an internship with some science firm that had the kind of name that screams "Subsidiary of LexCorp!" His boss was going to be Ms. Dominus so she was probably mutated in the events of Metal as well and will become his nemesis. I probably won't ever know if I was right about this guess because I will not be buying Issue #2. I made that promise to myself when I bought this issue. I was all, "Hey, fatty. You're only getting this one for the schadenfreude. Don't even think about buying a second issue of this crap." I agreed with myself and wiped the tears from my eyes before buying the book. Why was I always so mean to myself?

The issue ends with Sideways announcing himself to the world via YouTube. But as he's doing it, some cosmic entity appears and tells him to stop because he's endangering all time and space. But Sideways is a teenager so he's all, "Who the fuck are you? YOU AREN'T MY FATHER! I mean, I don't think you are. Are you?!"

Sideways #1 Rating: This comic book might fool some people into thinking it's interesting and cool. But actually it's just another book about a teenaged superhero who wants to do whatever the fuck they please. Ostensibly, they usually want to help society. Invariably, they wind up just fighting people who come out of the woodwork to fight them specifically. And this comic book doesn't disappoint in Sideways' first encounter! I won't be getting issue #2 but I hope the person encountering Sideways is all, "Dude. We've seen this before an almost infinite amount of times. The thing you're doing? It breaks universes. You have to stop." And then Sideways will be all, "Stop?! No way! I'm the perky young upstart rebelling against anybody telling me that their are limits to the things I want to do! Fuck you!" Then the alien guy will be all, "I tried to warn you!" And then Sideways will be all "RIFT RIFT RIFT RIFT RIFT RIFT DESTROY THE UNIVERSE!" and the series will end.

Action Comics #997

By Jurgens, Booth, Rapmund, and Dalhouse

Sideways' best friend is Ernestine. She's the exact character an old person would come up with after doing a bunch of research on Tumblr if that old person were making a character to connect with the kids. She's got her own unique style that's actually just pop culture camouflage hiding whatever her true personality is. I suppose the true personality is that she loves things so much that she squeeeees. She's the person who feels they have to be the biggest fan of everything to show how perky and different they are. She also wears a tiger skin onesie to school. And just to make sure that the readers understand just how outside of "normal" societal standards she is, she has a twin sister who totally dresses like mainstream America expects teenage girls to dress! She's got the regular pants and the regular shirt and the regular half-jacket and the regular shades on her regular blonde head. She also makes sure to point out that Ernestine's outfit isn't appropriate for school. In other words, she's a Popular. And us comic book reading nerds understand that they're the bad guys!

Sideways, like The Flash, is always late. That's a hilarious character defect for somebody who can be anywhere instantaneously! I bet Dan DiDio chuckled for five minutes thinking up that character trait.

Sideways is a brown boy named Derek who was adopted by an upper middle class white couple. Didn't society agree three decades ago that this was a racist trope? Weren't white people's lust for rescuing the non-whites satiated by Diff'rent Strokes and Webster? I suppose if I wanted to be upbeat with my hot takes on old television shows, I could set forth the theory that the vivacious and culturally eccentric personalities of the young minorities helped save the white people from living boring and mediocre lives in a loveless vacuum! That was the premise of Punky Brewster and that was practically the same show minus the eternally childlike black children from the other shows.

Speaking of terrible comic book tropes that never die (which is what makes them tropes! Geez! Get a dictionary, fatty! (HEY!)), Derek seems to be a boy genius who was about to get an internship with some science firm that had the kind of name that screams "Subsidiary of LexCorp!" His boss was going to be Ms. Dominus so she was probably mutated in the events of Metal as well and will become his nemesis. I probably won't ever know if I was right about this guess because I will not be buying Issue #2. I made that promise to myself when I bought this issue. I was all, "Hey, fatty. You're only getting this one for the schadenfreude. Don't even think about buying a second issue of this crap." I agreed with myself and wiped the tears from my eyes before buying the book. Why was I always so mean to myself?

The issue ends with Sideways announcing himself to the world via YouTube. But as he's doing it, some cosmic entity appears and tells him to stop because he's endangering all time and space. But Sideways is a teenager so he's all, "Who the fuck are you? YOU AREN'T MY FATHER! I mean, I don't think you are. Are you?!"

Sideways #1 Rating: This comic book might fool some people into thinking it's interesting and cool. But actually it's just another book about a teenaged superhero who wants to do whatever the fuck they please. Ostensibly, they usually want to help society. Invariably, they wind up just fighting people who come out of the woodwork to fight them specifically. And this comic book doesn't disappoint in Sideways' first encounter! I won't be getting issue #2 but I hope the person encountering Sideways is all, "Dude. We've seen this before an almost infinite amount of times. The thing you're doing? It breaks universes. You have to stop." And then Sideways will be all, "Stop?! No way! I'm the perky young upstart rebelling against anybody telling me that their are limits to the things I want to do! Fuck you!" Then the alien guy will be all, "I tried to warn you!" And then Sideways will be all "RIFT RIFT RIFT RIFT RIFT RIFT DESTROY THE UNIVERSE!" and the series will end.

Action Comics #997

By Jurgens, Booth, Rapmund, and Dalhouse

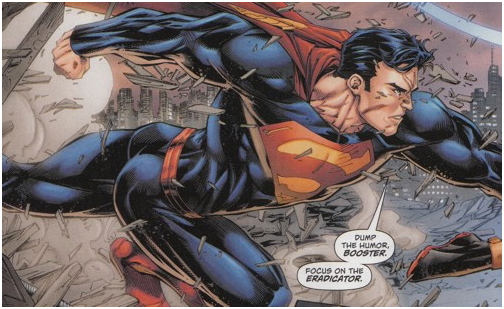

Superman with the rare male Boob/Butt Showcase.

I won't burden anybody who isn't reading this with any more of Brett Booth's terrible art or much of Dan Jurgens' terrible writing. Most of this is based on the premise that General Zod didn't get to raise his son because Zod's son was kept in the Phantom Zone. But since time doesn't pass in the Phantom Zone, how could that be? How did Zod's son grow up in the Phantom Zone? Have I been misunderstanding how the Phantom Zone works all this time or does Jurgens just think all comic book readers are morons? Sure, I think that as well! But I also know that they're full of the most useless facts, just ready to ambush Populars with a well-timed "Actually!"

Action Comics #997 Rating: This continues to be a terrible time travel story written by a writer who hasn't had a good idea since 1986 and drawn by an artist who thinks thighs should be, proportionally, thirty times bigger than every other body part. When DC Comics looks back at their history in the far future (and probably the really near future as well), they'll wonder why they chose such a terrible lead-in to their historic Issue #1000. Maybe they realized they already fucked it all up by renumbering Action Comics for The New 52 and just stopped caring.

DC Comics: "Technically this isn't really Issue #1000. Because of The New 52, Savage Dragon has more numerical continuity than all the DC books combined. We fucking suck."

DC Comics Fans: "More Harley Quinn please!"

Grunion Guy's Musical Corner of Music Reviews!

I still have a lot of comic books I want to write about but I'm approaching 5000 words and that's probably 4500 more than most of you are willing to read each week. Which means you aren't reading these words so why am I writing them? Unless you skipped all the comic book crap because you couldn't wait to hear my expert thoughts on songs that randomly came up on my iTunes.

Public Enemy Service Announcement #2 by Public Enemy

You're probably thinking, "Didn't you already review this in the last E!TACT newsletter?" Unless you weren't thinking that and you're now thinking, "Was that in the last newsletter? I didn't make it past the first five hundred words." Some of you who aren't reading this are probably not thinking but should be thinking, "I should check my spam folder for the last fourteen issues of E!TACT!"

To answer the first imaginary person's question, this is a different Public Enemy service announcement. Based on both of them coming up in two subsequent Grunion Guy's Musical Corners, you might conclude that I only have four albums on my iTunes. Well, I don't! I'm sure I have at least seven.

This announcement starts off boring with Chuck D not letting Flava Flav get a "BOOOOIIIIEEEEE!" in edgewise. But as soon as Chuck D shuts his yap about Black history being something we should celebrate daily, Flava Flav swoops in to rescue the announcement by saying, "Don't be a vulture! Learn your culture!"

Grade: B+

Angel with the Scabbed Wings by Marilyn Manson

This song is off Antichrist Superstar which is an album name that virtually ensured that I would purchase it, even if I hadn't already been told by Howard Stern that I had to like it. The entire album sounds like if a belt sander learned to play guitar while your menopausal aunt screeches about how her husband ruined her life by being a slovenly bore. Luckily, I like the way those things sound together.

This particular song seems to be about an angel with a nasty STD fucking the childbirth potential out of a bunch of virgins. I guess it's one of Manson's autobiographical songs?

iTunes categorizes this song as "alternative" because it doesn't have an "angry at the entire stupid world" genre.

Grade: B

Boy Scoutz in the Hood (Medley) by The Simpsons

The Simpsons aren't really a band which is fine because this isn't really a song. It's mainly a long clip from an episode of the cartoon. There is a bit of a "New York, New York" parody in the middle of the clip but it's not enough to keep from skipping this when it shuffles to the top. I think it made it onto the Songs in the Key of Springfield album because whoever came up Homer's line about weaselling out of things being the thing that separates humans from animals (except the weasel) produced the album. It's not as bad as the clip where Homer reads the ingredients in a jar of peanuts but it's pretty close.

Grade: D+

TV Sucks ("A Fish Called Selma" episode) by The Simpsons

Jesus Christ, iTunes. Every time I do one of these Music Corners, you're going to force me to spend one entire review bitching about your terrible random number generator, aren't you? I get that there is no perfect system for generating random numbers via computer programming. But you could at least spend a little money on product development so that it doesn't pull this shit! Especially since now I have to remember that there is a whole other "song" on this dumb album that's as bad as Homer reading peanut ingredients! At least the Boy Scoutz medley had a little music in it!

Grade: F

The Anarchist by Rush

Hmm. How am I supposed to grade a song that I've never listened to the entire way through? Am I going to have to do that now? I suppose I knew I would give Clockwork Angels an undeserved chance at some point. The main reason I own this album was that Rush put the digital version on sale for ninety-nine cents. I thought, "Well, how can you go wrong at that price?!"

What I learned immediately after was that maybe I should stop asking rhetorical questions that quickly have a long list of answers. The long list of answers for the question "How can you go wrong at that price?" is just a listing of the songs on this album.

The song is seven minutes of prog rock prog rockiness. It has a bunch of changes that actual music reviewers would probably understand and possibly praise. But I just listened to the song and thought five times, "Oh, is this a new song? Oh wait. No. Still The Anarchist."

The album comes with a booklet that apparently adds a short story element to the album. Maybe the reason I've never given this album a chance is that I've never read the story excerpts or listened to the album in the correct order (or at all).

I think maybe this album was just meant for die-hard Rush fans.

Grade: C-

I don't have any space for letters this month! I mean, I do since this is just a virtual newsletter. But I already went way too long and now my record word count of nearly six thousand words is going to set a new bar for my inability to not shut up.

Grunion Guy logging off! Is that a good sign off? What about "Goodbye, jerkos!"? Ooh! I like that better.

Goodbye, jerkos!

Action Comics #997 Rating: This continues to be a terrible time travel story written by a writer who hasn't had a good idea since 1986 and drawn by an artist who thinks thighs should be, proportionally, thirty times bigger than every other body part. When DC Comics looks back at their history in the far future (and probably the really near future as well), they'll wonder why they chose such a terrible lead-in to their historic Issue #1000. Maybe they realized they already fucked it all up by renumbering Action Comics for The New 52 and just stopped caring.

DC Comics: "Technically this isn't really Issue #1000. Because of The New 52, Savage Dragon has more numerical continuity than all the DC books combined. We fucking suck."

DC Comics Fans: "More Harley Quinn please!"

Grunion Guy's Musical Corner of Music Reviews!

I still have a lot of comic books I want to write about but I'm approaching 5000 words and that's probably 4500 more than most of you are willing to read each week. Which means you aren't reading these words so why am I writing them? Unless you skipped all the comic book crap because you couldn't wait to hear my expert thoughts on songs that randomly came up on my iTunes.

Public Enemy Service Announcement #2 by Public Enemy

You're probably thinking, "Didn't you already review this in the last E!TACT newsletter?" Unless you weren't thinking that and you're now thinking, "Was that in the last newsletter? I didn't make it past the first five hundred words." Some of you who aren't reading this are probably not thinking but should be thinking, "I should check my spam folder for the last fourteen issues of E!TACT!"

To answer the first imaginary person's question, this is a different Public Enemy service announcement. Based on both of them coming up in two subsequent Grunion Guy's Musical Corners, you might conclude that I only have four albums on my iTunes. Well, I don't! I'm sure I have at least seven.

This announcement starts off boring with Chuck D not letting Flava Flav get a "BOOOOIIIIEEEEE!" in edgewise. But as soon as Chuck D shuts his yap about Black history being something we should celebrate daily, Flava Flav swoops in to rescue the announcement by saying, "Don't be a vulture! Learn your culture!"

Grade: B+

Angel with the Scabbed Wings by Marilyn Manson

This song is off Antichrist Superstar which is an album name that virtually ensured that I would purchase it, even if I hadn't already been told by Howard Stern that I had to like it. The entire album sounds like if a belt sander learned to play guitar while your menopausal aunt screeches about how her husband ruined her life by being a slovenly bore. Luckily, I like the way those things sound together.

This particular song seems to be about an angel with a nasty STD fucking the childbirth potential out of a bunch of virgins. I guess it's one of Manson's autobiographical songs?

iTunes categorizes this song as "alternative" because it doesn't have an "angry at the entire stupid world" genre.

Grade: B

Boy Scoutz in the Hood (Medley) by The Simpsons

The Simpsons aren't really a band which is fine because this isn't really a song. It's mainly a long clip from an episode of the cartoon. There is a bit of a "New York, New York" parody in the middle of the clip but it's not enough to keep from skipping this when it shuffles to the top. I think it made it onto the Songs in the Key of Springfield album because whoever came up Homer's line about weaselling out of things being the thing that separates humans from animals (except the weasel) produced the album. It's not as bad as the clip where Homer reads the ingredients in a jar of peanuts but it's pretty close.

Grade: D+

TV Sucks ("A Fish Called Selma" episode) by The Simpsons

Jesus Christ, iTunes. Every time I do one of these Music Corners, you're going to force me to spend one entire review bitching about your terrible random number generator, aren't you? I get that there is no perfect system for generating random numbers via computer programming. But you could at least spend a little money on product development so that it doesn't pull this shit! Especially since now I have to remember that there is a whole other "song" on this dumb album that's as bad as Homer reading peanut ingredients! At least the Boy Scoutz medley had a little music in it!

Grade: F

The Anarchist by Rush

Hmm. How am I supposed to grade a song that I've never listened to the entire way through? Am I going to have to do that now? I suppose I knew I would give Clockwork Angels an undeserved chance at some point. The main reason I own this album was that Rush put the digital version on sale for ninety-nine cents. I thought, "Well, how can you go wrong at that price?!"

What I learned immediately after was that maybe I should stop asking rhetorical questions that quickly have a long list of answers. The long list of answers for the question "How can you go wrong at that price?" is just a listing of the songs on this album.

The song is seven minutes of prog rock prog rockiness. It has a bunch of changes that actual music reviewers would probably understand and possibly praise. But I just listened to the song and thought five times, "Oh, is this a new song? Oh wait. No. Still The Anarchist."

The album comes with a booklet that apparently adds a short story element to the album. Maybe the reason I've never given this album a chance is that I've never read the story excerpts or listened to the album in the correct order (or at all).

I think maybe this album was just meant for die-hard Rush fans.

Grade: C-

I don't have any space for letters this month! I mean, I do since this is just a virtual newsletter. But I already went way too long and now my record word count of nearly six thousand words is going to set a new bar for my inability to not shut up.

Grunion Guy logging off! Is that a good sign off? What about "Goodbye, jerkos!"? Ooh! I like that better.

Goodbye, jerkos!