The next section begins sometime in Slothrop's future. Some time has passed since his conspiracy breakdown and loss of everything that kept him tethered to his former life, like his Hawaiian shirts and his gaudy ties and Tantivy Muffer-Mafick. He spends his days with Katje and studying German rocket blueprints, trying to discover his connection to the rockets and, maybe, why They are doing what They're doing to him, whatever that is.

Stephen Dodson-Truck has arrived at the Casino. When he arrives, he interrupts Slothrop on the beach reading a Plasticman comic book. He might be there to spy on him. He might just be there because his wife was sick of looking at him and wanted to fuck everybody else at The White Visitation for awhile. But anyway, he gets to have some scenes for a few pages until we can all forget about him again until the next time when we'll ask, "Wait. Who was this guy again?"

Sir Stephen Dodson-Truck is into words. He's the Susie Dent of World War II. The introduction of Sir Stephen Dodson-Truck allows Pynchon to explain part of his process and love of writing directly to the reader. Pynchon's names are wacky but they often suggest other things, like Slothrop suggests (or directly states!) "sloth" and "slob". Stephen Dodson-Truck suggests (among maybe other things) Yerkes-Dodson law. This is what the Wikipedia entry on Yerkes-Dodson law states: "The law dictates that performance increases with physiological or mental arousal, but only up to a point. When levels of arousal become too high, performance decreases." I'm not sure how that fits in with Stephen Dodson-Truck's character but I'm sure it has something to do with sex and his wife, Nora Dodson-Truck. She probably needs some kind of level of super arousal after which his performance drops off which is why she needs to fuck all the other guys at The White Visitation. Pynchon explains how he makes these connections in the first conversation between Slothrop and Dodson-Truck. Slothrop begins the following conversation:

"Taking a break from that Telefunken radio control. That 'Hawaii I.' You know anything about that?"

"Only enough to wonder where they got the name from."

"The name?"

"There's a poetry to it, engineer's poetry . . . it suggests Haverie—average, you know—certainly you have the two lobes, don't you, symmetrical about the rocket's intended azimuth . . . hauen, too—smashing someone with a hoe or a club . . ." off on a voyage of his own here, smiling at no one in particular, bringing in the popular wartime expression ab-hauen, quarterstaff technique, peasant humor, phallic comedy dating back to the ancient Greeks. . . . Slothrop's first impulse is to get back to what that Plas is into, but something about the man, despite obvious membership in the plot, keeps him listening . . . an innocence, maybe a try at being friendly in the only way he has available, sharing what engages and runs him, a love for the Word.

Now doesn't that sound exactly like what Pynchon's doing, engaging with us in the only way he knows how while using peasant humor and phallic comedy and names that suggest these things all wrapped up in technical jargon and rocket lore?

Later, Slothrop meets with Katje in the gambling hall as she's manning a roulette wheel. He considers what They are betting on with him and he comes to a conclusion that they're basing all of their experiments (or whatever they're doing to him, exactly) on past observations. They know something about Slothrop's past life that even he doesn't know and now they want to see how that event plays upon his present actions. He then thinks about Katje's involvement in this plot and wonders how much she knows or how they might be manipulating her as well. And then there's a moment that mirrors a bit of Against the Day which I'm reading now. I'm going to quote both passages. First, Gravity's Rainbow:

Something was done to him, and it may be that Katje knows what. Hasn't he, in her "futureless look," found some link to his own past, something that connects them closely as lovers? He sees her standing at the end of a passage in her life, without any next step to take—all her bets are in, she has only the tedium now of being knocked from one room to the next, a sequence of numbered rooms whose numbers do not matter, till inertia brings her to the last. That's all.

And now, Against the Day:

From this height it was as if the Chums, who, out on adventures past, had often witnessed the vast herds of cattle adrift in ever-changing cloudlike patterns across the Western plains, here saw that unshaped freedom being rationalized into movement only in straight lines and at right angles and a progressive reduction of choices, until the final turn through the final gate that led to the killing floor.

In postmodern writing, you encounter a lot of images and metaphors of the Labyrinth. In these two passages, you get the exact opposite. You have people (and cows! But I think the cows really represent the immigrants of Chicago here! (hell, they really just represent us all and the aging process)) whose lives, while starting out full of freedom and choices, have come to that point where the previous choices made have cut off opportunities for further choice, winnowing their lives down to a single path which they can only follow helplessly until death. The cows have been forced into this kind of life just like the people of Chicago (earlier, the city had been described as being a Cartesian grid which the right angles and straight lines of the cow's Stockyard enclosure echo); life on the plains was a kind of freedom while life in the city a trudging journey along a single corridor maze to the killing room floor. Katje has sort of arrived at the same kind of place even though she's still young. But her choices have narrowed her chances at new opportunities faster than most: Blicero's sex slave, Allied spy, obligation to Prentice for rescuing her, Pointsman's tool, and now Slothrop's keeper. Not much choice for her in most of that. Just a roulette ball skipping about from number to number on a circular path, the number where it will eventually come to rest having no real meaning to the journey.

Dammit, Pynchon, I'm trying to read as much as possible before stopping and writing and he just won't let me go! Immediately after this initial conversation, Katje spins the roulette wheel again and we get the section that might be considered the titular bit. I must say, it's all a little too much for me. I get the part about how the rocket connected Katje and Slothrop; she was at the source, it's birth, while he was at the impact, its death, and between them the total life of the rocket. But I'm not sure what makes the parabola such a special shape that informs the connection between them, "as if it were the Rainbow, and they its children. . . ." I can also, maybe, grasp how they're children of the rocket, how all of us in the modern era are children of the rocket. The rocket that taught us death was not something you can prepare for or see coming; in the modern era, there is no languishing or regrets or remorse at the end. The end just comes, without warning. We become intrinsically different creatures, new children, from that knowledge hanging over us, from the dread of death come as surprise (which was obviously a thing at all times of human existence but not on such scale and not by something man has created and harnessed of their own volition). Perhaps the parabola represents the birth canal?

I'm just speculating here! Ha ha! That's a pun on speculum!

Later, when Slothrop chooses to grow a mustache, there's a moment where Pynchon himself (or some other narrator, not just omniscient of the story and era but out of time, from the future, from 1973, at least) intrudes.

"What kind?" Katje wants to know, soon as this one is visible.

"Bad-guy," sez Slothrop. Meaning, he explains, trimmed, narrow, and villainous.

"No, that'll give you a negative attitude. Why not raise a good-guy mustache instead?"

"But good guys don't have—"

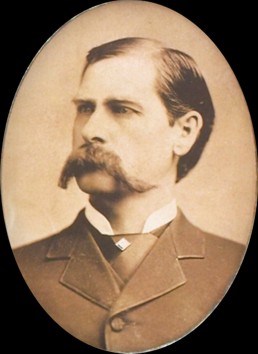

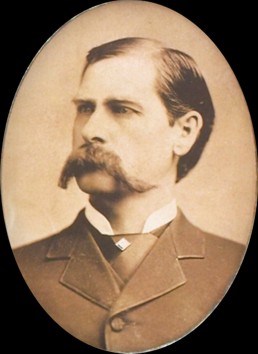

"Oh no? What about Wyatt Earp?"

To which one might've advanced the objection that Wyatt wasn't all that good. But this is still back in the Stuart Lake era here, before the revisionists moved in, and Slothrop believes in that Wyatt, all right.

The mustache Slothrop decides to grow

Stephen Dodson-Truck has arrived at the Casino. When he arrives, he interrupts Slothrop on the beach reading a Plasticman comic book. He might be there to spy on him. He might just be there because his wife was sick of looking at him and wanted to fuck everybody else at The White Visitation for awhile. But anyway, he gets to have some scenes for a few pages until we can all forget about him again until the next time when we'll ask, "Wait. Who was this guy again?"

Sir Stephen Dodson-Truck is into words. He's the Susie Dent of World War II. The introduction of Sir Stephen Dodson-Truck allows Pynchon to explain part of his process and love of writing directly to the reader. Pynchon's names are wacky but they often suggest other things, like Slothrop suggests (or directly states!) "sloth" and "slob". Stephen Dodson-Truck suggests (among maybe other things) Yerkes-Dodson law. This is what the Wikipedia entry on Yerkes-Dodson law states: "The law dictates that performance increases with physiological or mental arousal, but only up to a point. When levels of arousal become too high, performance decreases." I'm not sure how that fits in with Stephen Dodson-Truck's character but I'm sure it has something to do with sex and his wife, Nora Dodson-Truck. She probably needs some kind of level of super arousal after which his performance drops off which is why she needs to fuck all the other guys at The White Visitation. Pynchon explains how he makes these connections in the first conversation between Slothrop and Dodson-Truck. Slothrop begins the following conversation:

"Taking a break from that Telefunken radio control. That 'Hawaii I.' You know anything about that?"

"Only enough to wonder where they got the name from."

"The name?"

"There's a poetry to it, engineer's poetry . . . it suggests Haverie—average, you know—certainly you have the two lobes, don't you, symmetrical about the rocket's intended azimuth . . . hauen, too—smashing someone with a hoe or a club . . ." off on a voyage of his own here, smiling at no one in particular, bringing in the popular wartime expression ab-hauen, quarterstaff technique, peasant humor, phallic comedy dating back to the ancient Greeks. . . . Slothrop's first impulse is to get back to what that Plas is into, but something about the man, despite obvious membership in the plot, keeps him listening . . . an innocence, maybe a try at being friendly in the only way he has available, sharing what engages and runs him, a love for the Word.

Now doesn't that sound exactly like what Pynchon's doing, engaging with us in the only way he knows how while using peasant humor and phallic comedy and names that suggest these things all wrapped up in technical jargon and rocket lore?

Later, Slothrop meets with Katje in the gambling hall as she's manning a roulette wheel. He considers what They are betting on with him and he comes to a conclusion that they're basing all of their experiments (or whatever they're doing to him, exactly) on past observations. They know something about Slothrop's past life that even he doesn't know and now they want to see how that event plays upon his present actions. He then thinks about Katje's involvement in this plot and wonders how much she knows or how they might be manipulating her as well. And then there's a moment that mirrors a bit of Against the Day which I'm reading now. I'm going to quote both passages. First, Gravity's Rainbow:

Something was done to him, and it may be that Katje knows what. Hasn't he, in her "futureless look," found some link to his own past, something that connects them closely as lovers? He sees her standing at the end of a passage in her life, without any next step to take—all her bets are in, she has only the tedium now of being knocked from one room to the next, a sequence of numbered rooms whose numbers do not matter, till inertia brings her to the last. That's all.

And now, Against the Day:

From this height it was as if the Chums, who, out on adventures past, had often witnessed the vast herds of cattle adrift in ever-changing cloudlike patterns across the Western plains, here saw that unshaped freedom being rationalized into movement only in straight lines and at right angles and a progressive reduction of choices, until the final turn through the final gate that led to the killing floor.

In postmodern writing, you encounter a lot of images and metaphors of the Labyrinth. In these two passages, you get the exact opposite. You have people (and cows! But I think the cows really represent the immigrants of Chicago here! (hell, they really just represent us all and the aging process)) whose lives, while starting out full of freedom and choices, have come to that point where the previous choices made have cut off opportunities for further choice, winnowing their lives down to a single path which they can only follow helplessly until death. The cows have been forced into this kind of life just like the people of Chicago (earlier, the city had been described as being a Cartesian grid which the right angles and straight lines of the cow's Stockyard enclosure echo); life on the plains was a kind of freedom while life in the city a trudging journey along a single corridor maze to the killing room floor. Katje has sort of arrived at the same kind of place even though she's still young. But her choices have narrowed her chances at new opportunities faster than most: Blicero's sex slave, Allied spy, obligation to Prentice for rescuing her, Pointsman's tool, and now Slothrop's keeper. Not much choice for her in most of that. Just a roulette ball skipping about from number to number on a circular path, the number where it will eventually come to rest having no real meaning to the journey.

Dammit, Pynchon, I'm trying to read as much as possible before stopping and writing and he just won't let me go! Immediately after this initial conversation, Katje spins the roulette wheel again and we get the section that might be considered the titular bit. I must say, it's all a little too much for me. I get the part about how the rocket connected Katje and Slothrop; she was at the source, it's birth, while he was at the impact, its death, and between them the total life of the rocket. But I'm not sure what makes the parabola such a special shape that informs the connection between them, "as if it were the Rainbow, and they its children. . . ." I can also, maybe, grasp how they're children of the rocket, how all of us in the modern era are children of the rocket. The rocket that taught us death was not something you can prepare for or see coming; in the modern era, there is no languishing or regrets or remorse at the end. The end just comes, without warning. We become intrinsically different creatures, new children, from that knowledge hanging over us, from the dread of death come as surprise (which was obviously a thing at all times of human existence but not on such scale and not by something man has created and harnessed of their own volition). Perhaps the parabola represents the birth canal?

I'm just speculating here! Ha ha! That's a pun on speculum!

Later, when Slothrop chooses to grow a mustache, there's a moment where Pynchon himself (or some other narrator, not just omniscient of the story and era but out of time, from the future, from 1973, at least) intrudes.

"What kind?" Katje wants to know, soon as this one is visible.

"Bad-guy," sez Slothrop. Meaning, he explains, trimmed, narrow, and villainous.

"No, that'll give you a negative attitude. Why not raise a good-guy mustache instead?"

"But good guys don't have—"

"Oh no? What about Wyatt Earp?"

To which one might've advanced the objection that Wyatt wasn't all that good. But this is still back in the Stuart Lake era here, before the revisionists moved in, and Slothrop believes in that Wyatt, all right.

The mustache Slothrop decides to grow

If Slothrop lives in the time of Stuart Lake (the author of Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshall, 1931) who depicted Earp as an unrepentant hero of the West so that everybody in that era believed him to be a perfectly fine and upstanding law man who didn't exact any kind of personal vengeance through ambushes and slayings of the Red Dandy Hanky Gang, why even bring up the revisionist take on Wyatt and how one might argue his legacy? Unless maybe that revisionism had already started by 1945 in which case the narrator is just the usual kind of omniscient and felt like cutting off any reader arguments who would sneer at Katje's naivety. Although doesn't it sound like a 60s or 70s thing, that revisionism? Maybe it was a popular idea when Pynchon was writing this and decided to throw that comment in. But that line, "this is still back in the Stuart Lake era," is the proof that it's Pynchon, or at least a modern narrator speaking, right?

My point is that it's kind of weird! But I liked it, of course! Nice moment!

Slothrop discovers that he gets erections reading technical rocket manuals and blueprints. Perhaps the manuals, taken from German sites, were used around Imipolex. Or maybe it's part of the paradoxical or ultra-paradoxical or one of those other things that happen to Pavlov's dogs after long hours of being experimented on. I really never understood that psych stuff too well. Anyway, Stephen Dodson-Truck is always there during the study hours to time how long it takes for Slothrop to get a hardon.

Slothrop concocts a plan to get Sir Stephen drunk so that Stephen might spill some beans on the conspiracy. Dodson-Truck confesses that, as he got more and more lost in his work, the less he cared about satisfying his wife's urges (Yerkes-Dodson law, right?!) and so she began sleeping with the psychics and paranormals at The White Visitation. He mentions a son, whom I think might be being used as leverage to get him to participate in the Slothrop experiment, and admits his part in the conspiracy: he's meant to observe Slothrop to make sure Slothrop studies up on the rockets. And that's all he admits to knowing.

The scene switches, as it often does without warning to London and Eventyr (less warning than usual in this one although it is somewhat tied together by the image of some large hooded figures overlooking the land, and the Casino, somehow observing from the other side which connects them to, of course, Eventyr and Peter Sascha). One of Their operatives needs Eventyr's help but not the usual help of contacting somebody on the other side through Eventyr's control, Peter. No, this time, they're just interested in Peter. They know how Peter Sascha was killed in the street by police but now they want to find out how it came to that and how Leni Pökler may have led him there.

I can't say I completely understand this part but I get bits of it. Like how Peter sees his boring, pathetic life through the revolutionary actions of Leni, how he admits Leni is right when she says she can't be a mother to Ilse because she needs to be human for Ilse and being a mother is what They want. They have her at their mercy if she's a mother. So to protect Ilse, she cannot be a mother to her; she must be a revolutionary and a fighter and maybe she loses Ilse because of that but it can't be helped.

At the moment of Peter's death in the vision (or visitation?), the scene shifts back to the Casino with a mention that Dodson-Truck has vanished by morning. "But not before telling Slothrop that his erections are of high interest to Fitzmaurice House."

Dammit! I know Fitzmaurice House was recently mentioned but I can't remember when or where. Maybe it's not important!

By the end of this section, Katje has gone. Slothrop will never know why but before she goes, she tells him some stuff that he'll need to remember later. Hopefully I'll remember it too, if it's important. Although I've already read this once and I don't know how it's important now! So I might be a lost cause.

"Oh Slothrop. No. You don't want me. What they're after may, but you don't. No more than A4 wants London. But I don't think they know . . . about other selves . . . yours or the Rocket's . . . no. No more than you do. If you can't understand it now, at least remember. That's all I can do for you."

And later:

"Maybe you'll find out. Maybe in one of their bombed-out cities, beside one of their rivers or forests, even one day in the rain, it will come to you. You'll remember the Himmler-Spielsaal, and the skirt I was wearing . . . memory will dance for you, and you can even make it my voice saying what I couldn't say then. Or now."

Is she referencing one of Slothrop's final narrative moments in the book? Doesn't he play some instrument, camping in the rain, after fleeing from everybody's perception? I'll have to keep this in mind when I finally get there! It's only about five hundred plus pages away!

By the way, the skirt she references is a rainbow-striped dirndl skirt of satin. That could be important!

My point is that it's kind of weird! But I liked it, of course! Nice moment!

Slothrop discovers that he gets erections reading technical rocket manuals and blueprints. Perhaps the manuals, taken from German sites, were used around Imipolex. Or maybe it's part of the paradoxical or ultra-paradoxical or one of those other things that happen to Pavlov's dogs after long hours of being experimented on. I really never understood that psych stuff too well. Anyway, Stephen Dodson-Truck is always there during the study hours to time how long it takes for Slothrop to get a hardon.

Slothrop concocts a plan to get Sir Stephen drunk so that Stephen might spill some beans on the conspiracy. Dodson-Truck confesses that, as he got more and more lost in his work, the less he cared about satisfying his wife's urges (Yerkes-Dodson law, right?!) and so she began sleeping with the psychics and paranormals at The White Visitation. He mentions a son, whom I think might be being used as leverage to get him to participate in the Slothrop experiment, and admits his part in the conspiracy: he's meant to observe Slothrop to make sure Slothrop studies up on the rockets. And that's all he admits to knowing.

The scene switches, as it often does without warning to London and Eventyr (less warning than usual in this one although it is somewhat tied together by the image of some large hooded figures overlooking the land, and the Casino, somehow observing from the other side which connects them to, of course, Eventyr and Peter Sascha). One of Their operatives needs Eventyr's help but not the usual help of contacting somebody on the other side through Eventyr's control, Peter. No, this time, they're just interested in Peter. They know how Peter Sascha was killed in the street by police but now they want to find out how it came to that and how Leni Pökler may have led him there.

I can't say I completely understand this part but I get bits of it. Like how Peter sees his boring, pathetic life through the revolutionary actions of Leni, how he admits Leni is right when she says she can't be a mother to Ilse because she needs to be human for Ilse and being a mother is what They want. They have her at their mercy if she's a mother. So to protect Ilse, she cannot be a mother to her; she must be a revolutionary and a fighter and maybe she loses Ilse because of that but it can't be helped.

At the moment of Peter's death in the vision (or visitation?), the scene shifts back to the Casino with a mention that Dodson-Truck has vanished by morning. "But not before telling Slothrop that his erections are of high interest to Fitzmaurice House."

Dammit! I know Fitzmaurice House was recently mentioned but I can't remember when or where. Maybe it's not important!

By the end of this section, Katje has gone. Slothrop will never know why but before she goes, she tells him some stuff that he'll need to remember later. Hopefully I'll remember it too, if it's important. Although I've already read this once and I don't know how it's important now! So I might be a lost cause.

"Oh Slothrop. No. You don't want me. What they're after may, but you don't. No more than A4 wants London. But I don't think they know . . . about other selves . . . yours or the Rocket's . . . no. No more than you do. If you can't understand it now, at least remember. That's all I can do for you."

And later:

"Maybe you'll find out. Maybe in one of their bombed-out cities, beside one of their rivers or forests, even one day in the rain, it will come to you. You'll remember the Himmler-Spielsaal, and the skirt I was wearing . . . memory will dance for you, and you can even make it my voice saying what I couldn't say then. Or now."

Is she referencing one of Slothrop's final narrative moments in the book? Doesn't he play some instrument, camping in the rain, after fleeing from everybody's perception? I'll have to keep this in mind when I finally get there! It's only about five hundred plus pages away!

By the way, the skirt she references is a rainbow-striped dirndl skirt of satin. That could be important!

No comments:

Post a Comment